Here's a Facebook app waiting to happen: can you name all 51 bloggers currently doing time in Chinese prisons [1]? Any guesses what #52's last blog post will have been about?

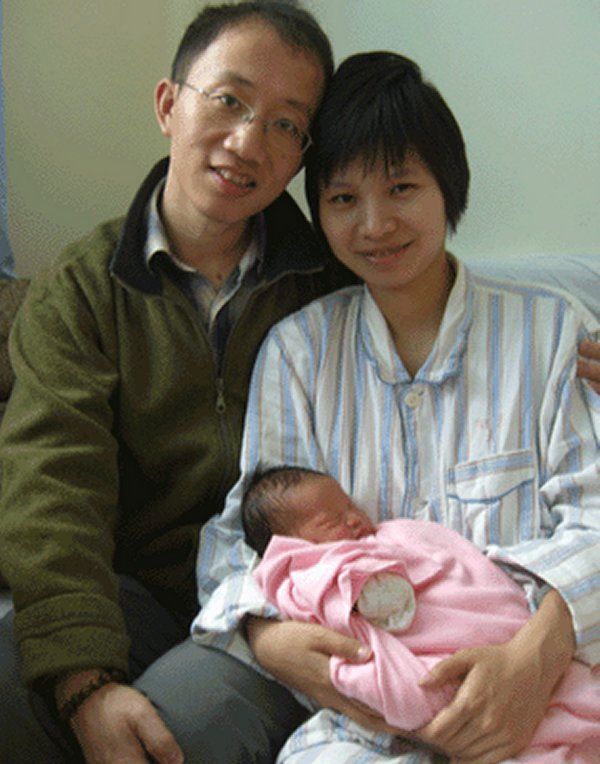

For house-arrested Hu Jia [2] in Beijing, it was his firsthand news [3] last week that Guangzhou [4]-based Zhang Qing, wife of imprisoned lawyer Guo Feixiong [5], had on Dec. 26 discovered that the roughly USD 1,000 left in her bank account had disappeared. No time like the present, Hu Jia [6] was arrested the next day in the middle of a Skype chat while his wife Zeng Jinyan [7] was in the bathroom giving their month-old baby a bath. Ten or more police had forced their way in, disconnected all communications in the house, and left, placing 24 year-old Zeng [8] and baby under house arrest, where they most likely still remain today.

Despite Zeng having been chosen last year [9] as one of the world's most influential people, the couple doesn't get blogged about much [10] in China.

Which is not to say never; blogger-historian and book critic Ran Yunfei chose Hu as one of China's ten people of 2007 in his Jan. 2 post [11]:

If our country is ever to change for the better, more Chinese people must be working tirelessly toward that. A few elites raising their arms and shouting, even when gathered, are not going to be able to solve the many and complicated social problems. Just like with the problem in Xiamen [12], if it had only been intellectuals like Zhao Yufen [13] and Lian Yue [14] making efforts, and if the people of Xiamen hadn't gone out to protest and march, the overall bargaining power would have been insufficient. But the people of Xiamen did get out and protest and march, and it was reasonable and orderly, something it's quite worth for people from all across China to learn from. At the same time, the Xiamen officials’ approach is an experience and lesson worth learning from for most local governments, even the central government.

Officially recognized people of the year are of course different from mine. The people I've recognized are recognized for their tireless and rational efforts efforts, recognized for our common call for democracy and freedom. Of the ten people I've chosen, as far as I know, three (Guo Feixiong, Chen Guangcheng and Hu Jia) are now in prison, and as it is the coming of the a new year, I hope that all the seeds of civil rights and resistance that they have scattered take root and blossom.

The people I've chosen are listed in no particular order, and even these ten people alone cannot make up for all the Chinese people I want to name, but what can I do, quotas have their limits. My assessment of them is temporary and impromptu at best, so not necessarily sufficient, but at the very least shows my respect. My hope for the Chinese people in 2008: less catastrophe, and more happiness.

In lieu of Ran's brief descriptions of each, links have been provided for background where available, and his choices are: Gao Yaojie [15], Zhou Yunpeng [16], Lian Yue [17], Wang Zhaojun [18], Gao Zhisheng [19], Guo Feixiong [20], Hu Jia [21], Chen Guangcheng [22], Pu Zhiqiang [23] and Mao Yushi [24].

Several of them, not just those in jail, don't often get blogged about, which is not to suggest bloggers don't try. Ran even left a comment on his post showing the automated message his blog host Tianya [25] sent him as he submitted it, warning him that it contained sensitive keywords and an administrator would be inspecting it shortly.

Following Hu's apprehension, a number of people have spoken out. Blogspot blogger Huang Yiyu writes of recent experiences in blogging about Hu in a January 2 post [26]:

I just want to say a bit about blogging. That no-one reads blogspot, I can of course understand (it having been harmonized by the Golden Shield [27]), but it's new waves of visits that strike me as very strange.

Of course I have no hopes of getting comments, so I'll just mention readership rates. There was a while during which the number of views on each post was consistently 10, never more, never less. Then after I deleted all the un-harmonious [28] posts, it seemed like there was only one, or sometimes none. When I only just made notes about my ordinary life, about how stupid or ugly I am, or how little money I have, it didn't have much appeal, and that nobody read those posts was quite common.

The strange thing is this: 17 people read my post on Dec. 31, a historically high number. There wasn't anything substantial in this post at all, so you can't say it was either well-written, nor pornographic and violent. Normally, nobody would have read it, yet it got seventeen views, very strange indeed.

As there are no comments, I of course have no idea who it was that came and read it, all I have to go by are the numbers. Personally, I think these 17 people were most likely internet police [29] of some sort, and because I put keywords like ‘Hu Jia’, ‘arrested’, ‘China’, together, and because of that was being watched. Several minutes after I submitted the post, it must have been like being at home with the Simpsons [30]: the Golden Shield alarm starts wailing, alerting the police, and everyone gets excited and rushes to the scene. Then the 17 people showed up, only to see it wasn't anything important, not pornographic or violent, and so the alarm got turned off. Anyway, I have a record high readership on that post [31].

Is a post of three lines something worth being so paranoid about? Maybe if you're blogger Guo Weidong, who in large font on his personal blog WRITES [32]:

Call on the Beijing government!

Immediately release Hu Jia!

The Chinese people, shackled in chains, welcome the Olympics!

And on his blogspot blog [33]:

Who is Hu Jia? What did he do?

How did he “incite to subvert state power”?

What is the Beijing government scared of?

Well-known sports journalist and Bullog International [34] blogger Wang Xiaoshan merely posted a picture of Hu in an post of eponymous name, with a link to neighbor blogger and Beijing publisher Mo Zhixu [35]‘s post, “An open China needs him” [36]:

I haven't met Hu Jia but for a few times, and how deep an impression was left; it was the year before last, just after he'd come out from over a month of imprisonment. Hu Jia, at the the time, despite the hardship he'd just been through, was as of old looking calm and collected, and very healthy. Because I'd always been worried about the safety of friends involved in the rights struggle and hunger strikes. Seeing that he'd finally been let out, and was being left alone, I was so happy that I sat down and wrote something about it, thinking that this could only be seen as a step forward.

From then on we mostly kept in touch over the phone or on MSN Messenger, the reason being that he was always on and off under house arrest. Even so, whether it was in Linyi [38] in Shandong [39] or at the door to lawyer Gao [19]‘s home, whenever friends and I heard any news or wanted to get some out, the first person we'd think of was Hu. My friend Peng Dingding [40] once went to his house to visit, but he couldn't even get to the door, and so it went on, with Hu's home in BoBo Freedom City in Beijing's Tongzhou [41] district to a very large degree becoming a news distribution center. We're the free ones, and yet we have to get our information from someone under house arrest. It sounds twisted, but that's just how valuable Hu Jia is.

[…]

It's risky when there's political dissent in an authoritarian society, when the rulers can do whatever they choose, this is quite plain. But this is the reason why most dissenters always try to keep a check on what they say and do, and work persistently towards lasting breakthroughs—even if they are just tiny, small breakthroughs. As I see it, the things that Hu Jia does haven't gone beyond this limit. The information he sends out, even if not sent out by him, could still not be locked away. Don't forget, this is the the cellphone and internet age. As for the verbal lashing he gives the secret police, it's nothing more than anger at being kept under illegal house arrest, and compared to illegal house arrest, which after all is the more despicable? Of all the things Hu Jia has done this year, as I see it, there hasn't been a shred of anything which could be said to be subversive. It's just been him upholding certain values of his.And it's just for that reason that Hu Jia's actions are fairly well-received. Not long before he was arrested, he even received the “China prize” human rights award from Reporters Without Borders. The common speculation now is that Hu Jia was arrested in order to take out some non-harmonious noise prior to the Olympics. This, though, I don't get, how a celebration held to send a message to the world—and it stands to be a very intense message—has anything to do with tiny, little Hua Jia being locked away and covered up. Seeing as how China has opted to open up, coming to embrace freedom is inevitable, and within openness and freedom there will always be different voices. Never mind that these kinds of voices will give birth to an even more open and free society, but just say that these voices were void of value and even annoying; isn't their existence alone simply the most effective defense of openness and freedom? Isn't their existence alone simply the best propaganda for “an open China welcomes the Olympics”?

New media activist Ai Xiaoming [42], who runs her own gender education BBS [43], has written an letter of her thoughts for the new year which has been reposted by MSN Live Spaces blogger Claire YW and is entitled, “public enemy of the state, or friend of the people?” [44]:

2008, a new year, marked by the shadow of Hu Jia's arrest. With friends, ‘happy new year’ this common greeting seems hard to say out loud. Happy for what? Jinyan and her month-old daughter, without any information at all, have lost Hu Jia. How are they supposed to get by? And when Hu Jia was being taken away, was he arrested like a drug dealer again, with a black sack thrown over his head? Was he stuffed under a car seat again, let to vomit until he nearly suffocated? Was he allowed to bring his liver cirrhosis medication? What's most worrying, is he going to be tortured and beaten up? Is he going to get the round-the-clock rotated interrogations? Is he going be cuffed for months on end until marks are left on his ankles? What's more, is he going to be beaten with electric batons like Guo Feixiong [45], until he has no more desire to live?

I can imagine all of these happening, but what could Jinyan be thinking? She's still so young, a year younger than my own child. Even in my dreams I see myself approaching her home, and I see her starving little daughter and the dim, eerie stairwell leading up.

Thankfully, today I saw news that the lawyer Li Jinsong will go meet with Hu Jia tomorrow, some relief for my anxiety. Compared to suspects who've long waited in vain to see a lawyer, Hu Jia's fate will be much better.

Writing of the one time Ai met Hu, at dinner following an AIDS seminar:

After that session, a bunch friends had dinner together. I sat just next to Hu Jia, and learned of his love for film. We even talked about the problems various film editing software have. A long while after that, I heard that Hu Jia and Jinyan had filmed their own documentary [46], “Prisoners in Freedom City” [47], which unfortunately I was only able to see a part of on someone else's computer. As a documentary maker myself, even though I only saw a part, I can still say with basic assurance, that this is an outstanding documentary. It documents personal lives, but it embodies the turning point of this era: individuals challenging the authority of the state.

[…]

Back to the topic of this post, Hu Jia and police keeping him under surveillance have been clashing for over a year now; the police keep him under surveillance on behalf of the state, but he just won't obey. It's in this way that Hu Jia became a public enemy of the state, or to put it more accurately, a public enemy of this authority mechanism. In the year just past, the “Hu Jia People's Broadcasting Channel” sent its news out over the internet quite late at night; I believe it was this information, in addition to his comments and views calling things for what they are, that compromised his crime of “subverting state power.”Yet, if you'll allow me to add a few words, I'm willing to say that Hu Jia's existence alone is the precise reason why this country cannot be subverted! Hu Jia's efforts have opened the door to positive and practical citizen journalism, as well as having given the world a window of hope: as long as Hu Jia exists, who is able to say that China is an authoritarian state? The constitution's promise to respect and uphold human rights had made a breakthrough, starting with Hu Jia's existence. I don't know, in Hu Jia's eyes, if such things as taboos even exist for him. Regardless, however, freedoms of speech for Chinese media, the internet and academia, because of the existence of Hu Jia, the kind of person who dared jump into the pit of fire, have already been greatly expanded. With people like Hu Jia, poking the butt of the tiger on a daily basis, the liberal intellectuals in their academies have woken up laughing from their dreams, and is there anything to be said more sensitive than that?

One line: the things which Hu Jia criticizes could all be improved. This country won't be overthrown, it just needs to thrive, keep on the up-and-up.

[…]

Now that Hu Jia is on the inside, so else is going to give warm clothing to the people freezing down on the streets? The miserable and vulnerable victims of injustice, victims of violent attacks, the political criminals that ordinary people don't dare get too near to, the family members of ‘faith criminals’. Who else can they phone straight up that will listen, that they can confide in with their sorrows? There were once several candles in the dark, but now, those who dare light one stands only to have it be snuffed out.From an arrest, to a lawyer's involvement, to a sentencing, there's still a short procedure to be followed. Legal representatives haven't been able to get out news on lawyer Gao [Zhisheng], they haven't been able keep Guo Feixiong from being tortured, or Chen Guangcheng from being sent off to labor camp, so in Hu Jia's state subversion case, how much will they be able to do? I personally am not staying optimistic, though I do know that there are a few facts that cannot change:

Regardless of how many years Hu Jia gets sentenced, his convictions will never change. Further, with his excellent wife, educated in human rights as she is, everything they go through will make its way known around the world.

Regardless of whether his defence will be able to reduce the punishment handed down to Hu Jia, the value in lawyers’ efforts will not change. Their role, defending citizens’ human rights, will gain precedent and experience.

Regardless of how many human rights workers still stand to have their voices silenced, it won't make suffering and crises disappear, instead only intensifying them.

As for the stakeout police keeping Hu Jia under surveillance, their tough duty has finally come to an end, and they can swap shifts. However, a year, two years, three or maybe ten or twenty years from now, after the tides of history have receded, how many citizens will stand up to defend their rights, and exercise those to the point where they become human rights workers? You may not have noticed at the time, but when the saying “rights defender” first came out, it was used by authorities in a negative sense; less than two years later, and rights defenders is a keyword used openly by media everywhere and has respectfully entered the realm of everyday language. People can transform words, just as much as they can create history.

Also, as the Chinese government, among international society, has signed one of the most important covenants from a United Nations human rights body, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights [48], it has the responsibility and obligation to create those conditions, and to to allow for this covenant to be carried out here in China, or else deal with international observers far more restricting than what was placed on Hu Jia.

FreeMoreNews, which provides original blogging on sensitive domestic stories, has a post today [49] that puts the number of police stationed outside Hu and Zeng's home as of January 2 at twenty to thirty, and mentions a visit from Hu's mother the same day. She was searched and had belongings confiscated upon going it, FMN writes, saw six police officers posted inside the home, and was herself visited later that evening and told not to accept any interviews or otherwise leak any information. Little else is known at this point. Defense lawyers Li Jinsong [50] and Li Fangping had applied to see Hu, and were denied [51] [zh]. The post does, however, list Hu Jia and Zeng Jinyan's home address:

#542, Unit 5, Building #76, BOBO Freedom City, Dongguoyuan [52], Tongzhou district, Beijing

北京通州区东果园BOBO自由城76号楼5单元542号