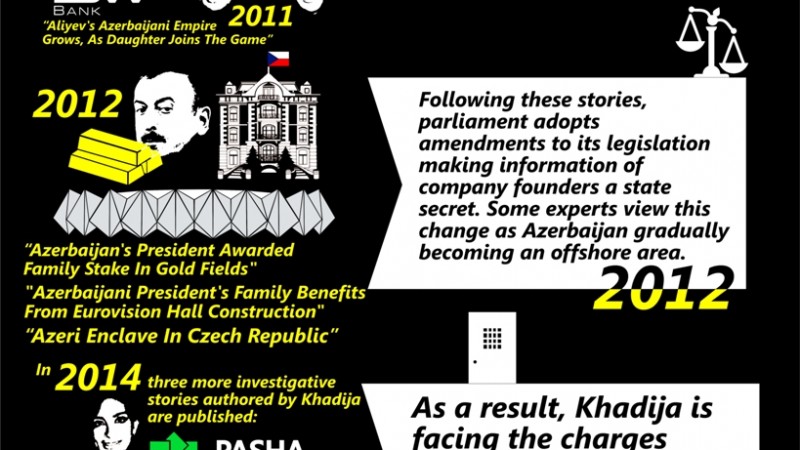

Section of an infographic detailing Khadija Ismayil's investigative journalism work and the charges she has faced for it. Originally published on Meydan TV. Republished with permission.

There is no such thing as failure in Azerbaijan. The country's upward trajectory is eternal and unstoppable.

Never mind that the country's president wins a Corruption Watchdog's ironic “Person of the Year” award. Or that the number of internationally-recognized political prisoners in the country's badly-kept jails is approaching one hundred.

Azerbaijan, an energy-rich Caspian state dominated by the ruling Aliev family since before the collapse of the Soviet Union, likes to burnish its international image. Puff articles selling the government's successes routinely appear in some of the world's biggest news outlets. It reveled in hosting the Eurovision song contest in 2012. It is set to host Formula One and the first edition of the European games next year.

The Dec. 5 arrest of 38-year-old investigative journalist Khadija Ismayil, on trumped up charges, will test the limits of this bright facade.

Azerbaijan's best-known political prisoner?

Ismayil, whose family name can also be rendered Ismayilova, is a smart and talented woman from Azerbaijan. Among her friends and colleagues she is known for her outspokenness, honesty and fearlessness. Outside Azerbaijan she is known for her outstanding work in exposing things the Azerbaijani government would prefer to stay a secret. Her expertise? The ruling family’s illicit — and very international — business empire.

News of her arrest, ordered by the Sabail District Court, was reported by outlets around the world on December 5. The #FreeKhadija hashtag soon trended on Twitter.

If Ismayil is incarcerated, she will be Azerbaijan's most globally famous political prisoner. She has received numerous international journalism awards and recognition for her investigations into corruption in the country. This is not the government's first attempt to silence Ismayil.

A thorn in Baku's side

When she first began exposing the Alievs’ financial dealings in 2010, she knew what her work would cost her. During a trip abroad in July 2011, someone — the case is still supposedly under investigation in Azerbaijan — entered her apartment and installed a number of security cameras. The installation occurred shortly after the publication of one of Ismayil's stories about the Aliyev family's business interests.

On March 7, 2012, Ismayil received an anonymous piece of mail by post containing intimate pictures of her and a letter warning that video footage of her having sex would be released on the Internet if she did not stop reporting. The note read: “Whore, behave. Or you will be defamed.” Ismayil did not stop. The video went online and was widely disseminated.

Her subsequent stories exposed more murky deals about the Alievs, shedding light on offshore and local companies owned by President Ilham Aliev's two daughters, as well as shady construction agreements.

By June 2012, due in no small part to Ismayil's reporting it became illegal to obtain company and ownership information in Azerbaijan. The parliamentary bill referred to “commercial secrets” but for the government’s critics this was a worrying sign: if obtaining information was difficult before, it was now a crime against the state, a fact that almost guarantees impunity for officials engaged in illicit business ventures.

Both Ismayil's lawyer and her accuser have been forced to sign gag orders pledging not to speak publicly on the case. Thus the current charges against her are not fully clear.

This past October, the journalist was accused of libel and slander by Elman Hasanov, a former member of the opposition Popular Front Party. An ex-security official informed Ismayil that Hasanov had been compromised by the government and used to infiltrate opposition circles.

Ismayil wrote on her Facebook page (currently deactivated as per her own request) that she had not revealed Hasanov's identity in the information she published:

This is a private prosecution complaint by Elman Hasanov […] He claims I published in Facebook page two documents which is libelous and slander against Elman Hasanov […] I didn’t publish any document which named Elman Hasanov. In October 2011 (five months before the sex tape blackmail against me) former investigator of the Ministry of National Security Ramin Nagiyev sent me a file [allegedly claiming] recruitment of Elman Hasanov [by the Ministry of National Security] as an agent inside the opposition […] I was unable to check the authenticity of the document […] In February 2014 following a TV show where I was accused of being a spy and when the former MNS official said they knew everything about me, I decided to publish the alleged document. But I erased name and any information which would help identify Elman Hasanov […] Later [I learned that] someone whose Facebook nickname was Mustafa Kozlu already published the full document without erasing the name. I urged people to respect people’s dignity and privacy and not share the name of the person.

Ismayil was summoned to the Prosecutor's Office the following day and accused of “revealing a state secret.”

Also in October 2014, Ismayil was detained for several hours by government officials at Baku airport after she discussed Azerbaijan's human rights record with officials from the Council of Europe.

The most recent charge against Ismayil — incitement to suicide (Article 125 of Azerbaijan's Criminal Code) — was brought by Tural Mustafayev, a journalist who briefly collaborated with the Azerbaijan service of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, where Ismayil worked previously. He was later hired by a different media outlet, Meydan TV and fired 3 months later for unprofessional behaviour.

Full disclosure: The author of this article is currently a journalism fellow at RFE/RL and English language editor at Meydan TV.

Mustafayev has stated that he attempted suicide on October 20 (by drinking rat poison) after Ismayil interfered with his professional development and threatened him on Facebook. According to sources close to the case, he has not provided evidence of these allegations.

What next for Azerbaijan?

The ongoing crackdown on free speech and human rights in Azerbaijan negates the millions the country's leadership has paid western PR firms to improve its international reputation.

The first set of charges against Ismayil were initiated in October 2014 while Azerbaijan was still holding its controversial chairmanship of the Committee of Ministers at the Council of Europe. Despite a few presidential pardons for political activists, its chairmanship, which began on May 13 and concluded November 13, proceeded amid flagrant violations of its international commitments.

While the Council of Europe reprimanded Azerbaijan for its rights record at the end of the chairmanship, tougher action must be taken as the country's governance and rule-of-law record reaches new lows.

The lavish caviar-laced dinners and impromptu galas and exhibitions Baku holds for western delegates should not obscure the fact that Azerbaijan's repression of domestic dissent is reaching new heights. Oil and gas should not be reasons to coddle an odious regime.

2 comments