Small Media assessed Internet policy during President Hassan Rouhani's first 18 months in office. Image created by Small Media and used with permission.

This post was written by Small Media researcher Kyle Bowen [1] based on the report [2] of the same name.

“Filtering has not even stopped people from accessing unethical websites. Widespread online filtering will only increase distrust between people and the state.”

These words [3], uttered by Iranian President Hassan Rouhani shortly after winning the 2013 election, raised hopes that the Iranian Internet was about to become a bit more free. For Iranian netizens, this was welcome news, as the final eighteen months of Ahmadinejad’s presidency were marked by a persistent tightening of restrictions on internet freedom.

In January 2012, strict rules [4] were introduced for cyber cafés, requiring owners to keep detailed records of patrons’ personal information and browsing history for at least 6 months. In March of that year, the Supreme Leader created the Supreme Council of Cyberspace (SCC) [5], a powerful and shadowy organisation with the ultimate say on all Internet policy matters. While the council is chaired by the president, it is dominated by conservatives. And in the early months of 2013 [6], government throttling reduced the Iranian internet to glacial speeds ahead of the June 14th election.

In this context of heightened restrictions and creeping censorship, Rouhani’s message of a more open internet struck a consonant chord with the Iranian public.

But has Rouhani lived up to these lofty expectations? This is the question Small Media’s latest report [2] sets out to address. This research looks at media perceptions, Iran’s censorship institutions, and three years of ICT budget data to put together an internet policy report card for Rouhani’s first 18 months in office. So how has he done so far?

The Good

One positive sign is Rouhani’s willingness to take on Iran’s internet censorship body [7], the rather verbosely-named Committee to Determine Instances of Criminal Content (CDICC). When the CDICC passed a motion ordering WhatsApp to be blocked, Rouhani advised his ICT minister Mahmoud Vaezi to refuse to implement it. Naturally, Iran’s censorship body did not respond well to such insubordination, with the CDICC’s hardline secretary Abdolsamad Khoramabadi claiming that Rouhani had no basis for challenging his committee’s directives. It was at this point that Vaezi pulled rank, pointing out that as chairman of the Supreme Council of Cyberspace, Rouhani’s say on the matter was final, and the block on WhatsApp would not be implemented. As of this writing, WhatsApp remains available in Iran, temporary disruptions notwithstanding.

Among other things, this political standoff over WhatsApp illustrated that Rouhani was serious about some of his campaign promises. What’s more, his intervention tangibly impacted Iran’s filtering policy, keeping WhatsApp available in the Islamic Republic. Rouhani’s decision to challenge the CDICC over the WhatsApp ban was certainly a step in the right direction. But when we turn to the ICT budget and examine Rouhani’s spending priorities, some troubling signs begin to emerge.

The Bad

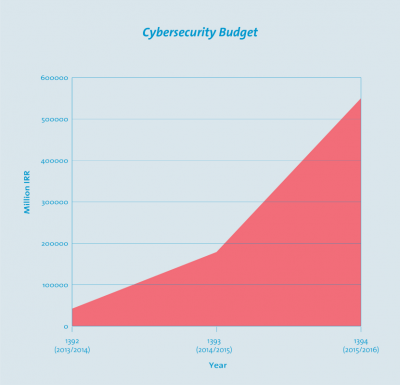

One potential cause for concern is the explosion of the cyber security budget. When Rouhani took office, cyber security funding stood at 42,073 million IRR (3.4 million USD). In the budget for the upcoming year, it has soared to 550,000 million IRR (19.8 million USD), an increase of over 1200% in just three years.

The ICT budget has increased of over 1200% in just three years. Image created by Small Media and used with permission

This vertiginous rise, which comes on the heels of the Stuxnet [8] and Flame [9] cyber attacks and the NSA spying scandal, shows that the government is making security a higher priority. There’s nothing wrong with that per se, but it raises the worry that vague security concerns will be cited to justify further restrictions on internet freedom. Indeed, Iran has a long history [10] of rationalising censorship based on the threat of Western cultural invasion [11]. And the NSA scandal has prompted numerous calls [12] to support Iran’s national internet, from hardliners [13] and reformists [14] alike.

Another problematic development concerns the ICT ministry’s full-throated support for both SHOMA (the national internet) and intelligent filtering. Last month, Rouhani’s ICT minister Mahmoud Vaezi announced [15] that he was courting private sector investment in SHOMA, perhaps [16] in an attempt to increase efficiency and expedite the development process. Vaezi also explained [17] that work on phase II of the intelligent filtering system began on January 28, after the successful completion of phase one. In January, a number of Iranian netizens complained [18] that testing of the intelligent filtering system disrupted their access to Instagram.

The Future

After assessing Rouhani’s ICT policies thus far, the report concludes with three predictions about the future of internet censorship in Iran. Here are a few things to look out for:

-

More fights over social messaging apps. Minister of Culture and Islamic Guidance Ali Jannati recently announced that 9.5 million Iranians [19] are on Viber. As these mobile apps continue to grow in popularity, blocking them will become an increasingly difficult proposition for elected representatives of Iran’s government. But that won’t stop the conservative judiciary from fighting tooth and nail to outlaw their use. We can expect more battles over the blocking of apps like Viber, pitting Iran’s moderate president against its hardline censorship institutions.

-

Iran is unlikely to be cut off from the global internet, partly because it’s a lifeline to tech entrepreneurs. Iran’s recent launch [20] of a domestic search engine, coupled with its development of a national internet prompted fears [21] that the Islamic Republic would soon be cut off from the World Wide Web. The government is certainly encouraging [22] Iranians to use domestic apps and platforms over which it has greater control. But it’s worth remembering that a substantial portion of Iran’s tech sector still depends on the global internet. For example, Blogfa [23], one of Iran’s most popular blogging platforms, is hosted in Canada. Moreover, lucrative Iranian startups such as Digikala [24] may soon look to expand to new markets or solicit foreign investment (Iran’s emergent startup scene has aroused [25] considerable interest [26] in the West [27]). Viewed from this angle, it’s clear that any long-term disconnection from the global internet could incur considerable economic and political costs for the Iranian government. Yet temporary disruptions [28] during politically sensitive [29] times are likely to continue.

-

Iranians are more concerned about internet access than online security. A recent survey [30] on VPN use in Iran found that Iranians flock to circumvention tools that are free and easy to use, while more secure (but less user friendly) VPNs such as Tor were not as popular. A previous Small Media study [31] reached a similar conclusion, finding that only 6.6% of respondents used VPNs for the primary purpose of enhancing personal security online. The preference for access over security makes sense when you consider what Iranians like to do online. As BBC Persian journalist Hadi Nili explains [30], “They want to listen to music, watch videos, download both, and update their Android or Apple devices… So even if they need a better security, they might opt to compromise their privacy for the price and ease of use.”

We can draw a couple of conclusions from these priorities. First, despite all the hype [32] about “Twitter Revolution” following the 2009 election, it seems quite plausible that most Iranians are be more interested in using the internet for entertainment rather than political activism. Second, Iranians’ somewhat blasé attitude towards online security will make VPN users much more susceptible to government surveillance. In the past couple of years there have been a series of arrests [31] related to VPN use in Iran. We can expect this crackdown to continue, and perhaps even accelerate after the launch of SHOMA.