This post was co-authored by Nani Jansen, legal director for the Media Legal Defence Initiative.

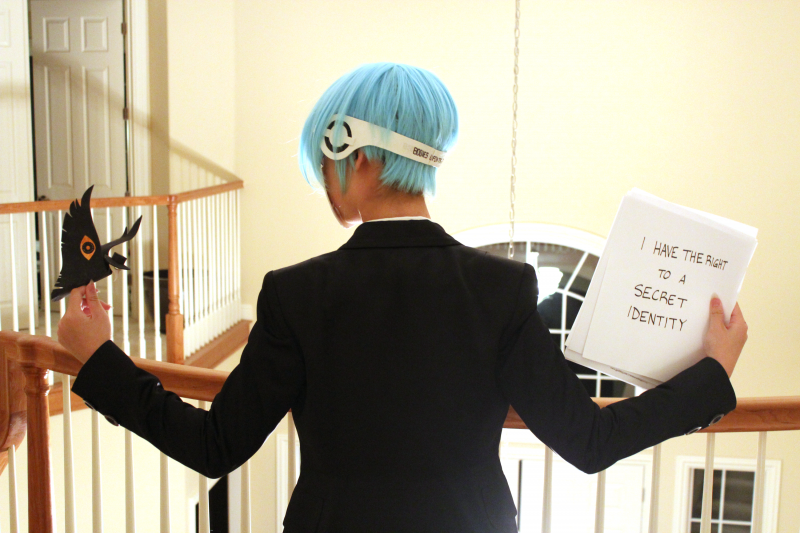

Should you be anonymous online? If you were giving advice to a blogger, independent journalist, or online activist on this issue, what factors would you want her to consider? Many of us have been through this process, but it is something we don’t talk about much, as it often happens in private spaces.

There’s been lots of debate about the impact of government and corporate policy on the issue — think of Facebook’s real name policy and Nymwars. And there is plenty of accessible information about how to protect one's anonymity online. Digital security trainings and guides abound, if only in certain languages.

But the decision-making process that comes before this often gets less attention. There are legal, technical, political, and personal issues in play, all of which are difficult to navigate. And there is no definitive “right” answer for anyone.

We've been struggling with this issue in the case of the Zone9 bloggers, the group of online activists who were arrested in Ethiopia in April 2014 and charged with trumped-up terrorism offenses. Although the bloggers regularly wrote under their real names, they had learned about secure communication technologies in an effort to keep their research and reporting processes private. Paradoxically, this has become part of the government's case against them — their use of Tactical Technology Collective's “Security in a Box” toolkit appears on their charge sheet.

A different example comes with the situation of bloggers in Cuba, where physical surveillance is so robust that online anonymity is often considered an unrealistic approach. In a 2009 interview with Global Voices, Cuban blogger Miriam Celaya explained:

…here it is more dangerous to remain “anonymous” by trying to hide. In this semi-clandestine state, one is more prone to blackmail. I was aware that the police knew my real face and could guess that I was scared…

Another Cuban blogger noted that it could actually make things worse. “By writing under a pseudonym,” she said, “we signal to the state police that [we] think we are doing something wrong.”

There are countless cases and examples that we could explore in an effort to help online writers and activists navigate this process. So next week, Global Voices and the Media Legal Defence Initiative will be hosting a discussion session on the topic at Re:Publica in Berlin. Our hope is to develop some guidelines for people facing this difficult question.

Before the event, we decided to take the conversation online, talking with the GV Advox team and our readers. Advoxers were quick to point out that the issue goes far beyond technical security. “[One must] reflect on self-censorship, ethics, personal safety, and personal limits…one thing is technical security, another is your mental and emotional stability,” said one author.

“There is an art to anonymous blogging,” said an author who had managed multiple online identities over time, sharing some personal information on semi-private platforms like Facebook, while keeping his identity as a blogger completely separate from this and other social media accounts. For many, this too can create an emotional toll, especially if political or personal circumstances change.

Another author talked about isolation in anonymity. “Anonymity also isolates you,” she wrote. “Can you have a network to protect you and also be anonymous at the same time? Would visibility be a better strategy for you?”

A digital security expert in the group raised the key distinction between “identity anonymity” and “location anonymity”. He explained the concept of “location anonymity” using an example from Bahrain:

We know that in Bahrain the authorities very commonly crack down on dissidents and journalists by luring them into clicking on links generally sent to them through social media (tweets or facebook messages for example)….they normally just see a news article (often from a legitimate website) being opened, [but] in the background, the link [obtains and records] the IP address of the victim and then redirects him/her to the legitimate news article.

The authorities [use] this method to obtain the [victim's] IP address…and through their control of state Internet and mobile providers verify the real identity of the user (in case he/she is using a fake name or an alias online) as well as his/her physical location. As you can imagine, this is then how raids and arrests follow.

In this situation for example, using an instrument like Tor would have prevented the authorities from obtaining the originating IP address. We all know the inherent risk of getting singled out by using Tor within an oppressing state. As it is now in Bahrain, I would consider not using Tor a worse choice, but I think this is a great example of the problem we're trying to address.

So now we want to pose the same question to our readers: What key questions would you suggest people ask themselves before making this decision? What stories might help us develop this discussion? What examples have we seen, that are publicly known, that could help bloggers and online activists navigate this difficult decision-making process? Tell us your thoughts here, on Twitter (tweet @Advox) or send a message through our contact form.

Nani Jansen and Ellery Roberts Biddle will lead a discussion workshop on this topic at Re:Publica in Berlin, on May 5, 2015 from 4-5pm. Please join us if you're there, or look out for further reporting on the issue after the event!

3 comments

Hi.

My question: In today’s online surveillance environment where a single operational misstep could reveal your identity (e.g. one hurried reply or viewing twitter.com without Tor) , what checklists exist, or should exist, to promote consistent use of required security tools?

I fully realize checklists aren’t very exciting and a multitude of guides already exist. But given the risks, concise, easy to follow and step-by-step procedures could make a big difference.

Thanks for sharing this post

Tim

When it deals with powerful people, eg millionnaire, this question is expendable… https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strategic_lawsuit_against_public_participation#France