From top to bottom, the logos of Parsijoo, Yooz, and GorGor. Mixed by Amin Sabeti.

This post was written by Small Media [1] researcher Kyle Bowen [2], and is based on Small Media's latest Iranian Internet Infrastructure and Policy (IIIP) report [3]. A version of this post was published on Medium [4].

Over the past few years, Iranian officials have championed ‘national’ tech development projects (such as the National Information Network (SHOMA) [5] and Iranian versions of Western services [6]), while eschewing foreign platforms like Viber and WhatsApp.

One of the most recent examples of this dynamic can be found in the February 2015 launch of three Iranian search engines: Parsijoo [7], Gorgor [8] and Yooz [9]. While this was announced in February, it should be noted that Parsijoo was in fact launched a few years ago, and Yooz was launched in early 2010. It’s unclear why the authorities are presenting them as “new”.

Government officials [10] insist that Iranians can use domestic search engines without any disruption from the filtering system, regardless of what terms they search for. The authorities also maintain that these search engines can compete with Google and other Western alternatives.

Small Media’s latest report [3] put these claims to the test. We picked six potentially keywords: ‘sex,’ Baha’i,’ ‘Mir Hossein Mousavi,’ ‘BBC Persian,’ ‘Facebook,’ and ‘VPN,’ and searched for them on the search engines mentioned above plus google. Here’s what we found:

Searching for…Sex

We couldn’t resist starting with such a potentially salacious keyword as “sex”. And the results didn’t disappoint. Perhaps most striking was the lack of results from Parsijoo, which greeted our query with a blank page.

What happens when you search for ‘sex’ on Parsijoo

The other Iranian search engines were a bit more forthcoming. GorGor’s first page of results included links to pages about erotic stories, various sex positions, and dire warnings about the dangers of anal sex. Yooz offered similar results, while also including a blog post about why some women do not like oral sex and a documentary about sex in a Sigheh [11], or temporary marriage.

Google took things a step further, providing links to pages with “sexy images,” and “the most viewed sex videos.” So sex-related searches seem to generate different results on Iranian search engines than they do on Google. But does this disparity hold when the keyword has to do with religion?

Searching Baha’i as a Keyword

We chose “Baha’i” as a religion-related keyword mainly because of the well-documented [12] history of persecution [13] Baha’is have suffered [14] in the Islamic Republic. Our findings here weren’t especially surprising. The results on all of the Iranian search engines were overwhelmingly hostile to Baha’is, with many referring to them as “the misguided Baha’i sect.”

Google, on the other hand, offers more balanced and neutral results: the top three results are from Wikipedia, the fourth is the website of the worldwide Baha’i community and the last 5 results are opposed to the faith. With sex and religion out of the way, let's now turn to politics. How did Iranian search engines deal with searches for Green Movement leader Mir Hossein Mousavi?

Searching for Mir Hossein Mousavi

Although Iranian search engines seem to pull in Mousavi-related Wikipedia pages indiscriminately, the majority of non-Wikipedia content on their front pages are news articles from before Mousavi’s house arrest, or editorials criticising his political activities. None of the articles concern his criticisms of the Ahmadinejad government, or claims of electoral fraud in 2009. More than 40% of Google’s front page results concern these topics.

Put another way, when Iranian search engines weren’t pulling content from Wikipedia, they seemed to be excluding results that might challenge the government’s line on sensitive political matters. Turning now to searches for BBC Persian, we encounter a more subtle and insidious form of censorship.

Searching for BBC Persian

Not only do Yooz and GorGor offer no links to either bbcpersian.com or bbc.co.uk/persian, but the majority of results on Yooz actually direct users to persianbbc.ir, which is a fake version of BBC Persian.

Links to the fake BBC Persian on Yooz

The real and fake BBC Persian pages look very similar. See if you can tell which is which. Here’s the first one, which we’ll call Image 1.

Image 1

And here’s the second, which we’ll call Image 2.

Screenshot of Image II.

Give up? Image 1 is the fake BBC Persian, and Image 2 is the real one. If you don’t speak Persian, you’d be forgiven for struggling with that question. But if we translate the top three headlines on each page from April 17, 2015, it gets a bit easier.

Top three headlines from the real BBC Persian:

- Pakistan’s Parliament disagrees with military operation in Yemen war

- Engine of Iran’s commercial aircraft exploded in Istanbul airport

- 7 Pakistanis killed in Syria were buried in Qom

Top three headlines from the fake BBC Persian:

- BBC insists on justifying crimes of terrorism in East of the country

- BBC tries to exploit death of Khatami’s mother

- BBC praises ISIS

While the real and fake BBC Persian pages look very similar, a look at the top three headlines for each reveals a sharp contrast in editorial orientation. It seems that Iranian search engines are trying to deceive users by sending them to fake pages filled with spurious and inflammatory stories. With searches for online social networks, a similar form of deception emerges.

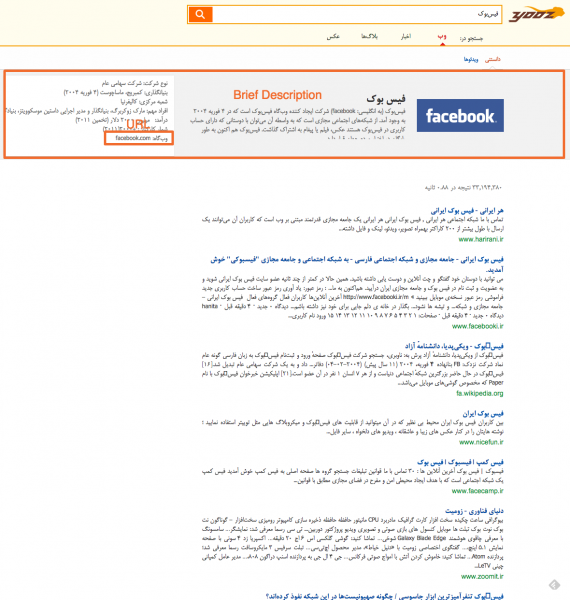

Searching for Facebook

As with BBC Persian, searches for social networks like Facebook and Twitter often direct users to artificial knock offs. For example, whenever users search on Parsijoo, Yooz or GorGor, they cannot find links to Facebook or Twitter. Instead, users are directed to Iranian versions of these websites via links such as: facebooki.ir, facecamp.ir, twittfa.ir.

While these search engines seem to be designed to hide the URLs for Facebook and Twitter from users, some of them actually display these URLs on the top of the results page. For instance, you cannot find Facebook.com among Yooz’s search results. However, the top of the results page contains a brief description of Facebook, followed by a link to Facebook.com.

Facebook description (and link) automatically imported from Wikipedia

While the search results try to direct users to Iranian social networks, the description at the top of the page contains a link that leads them straight to the real Facebook! It’s difficult to say whether this oversight stems from carelessness or incompetence, but it seems clear that such sloppy attempts at censorship wouldn’t be difficult for even the least tech savvy Iranians to circumvent. Speaking of circumvention, lets see how Iranian search engines handled queries for VPNs.

Searching for VPNs

Unlike most of the terms discussed above, the results for searches for VPN on Iranian search engines and Google are very similar, and include numerous video tutorials [15] regarding VPN use hosted on Apart, an Iranian version of YouTube. Yet while Iranian search engines don’t appear to censor results for VPN related searches, it is possible that when a user clicks on one of the links, he or she will be blocked from accessing the VPN selling site.

In any case, for all the filtering discussed above, it seems that Iranian search engines are surprisingly forthcoming as far as queries for circumvention tools are concerned.

What can we conclude from this?

It seems clear that domestic search engines form a new part of Iran’s vast internet filtering apparatus. As we have seen, searches for sensitive keywords, such as Baha’i, yield considerably different results on Iranian search engines than they do on Google.

For some users, this disparity is a good reason to distrust Iranian search engines. Their familiarity with Google’s results for a given search will make it easy for them to spot a heavily filtered domestic alternative. Moreover, the fact that Yooz carelessly included a link to Facebook at the top of its results page suggests that many netizens won’t have too much trouble circumventing censorship efforts. However, we can’t assume that all users will be so critical or astute.

Those users who credulously turn to Yooz, GorGor, and Parsijoo with their online queries could easily be lead to believe false or misleading information. Moreover, even critical netizens may struggle to tell the pages for the real BBC Persian and the fake one apart, as they look remarkably similar.

In an age when so much of what we know about the world comes from online media sources, exercising control over which websites users see and which ones they don’t endows search engines with considerable power. And when the Iranian government uses that power to promote a specific ideological agenda and exclude alternative viewpoints, the Internet freedom of Iranian citizens suffers.