The way the Mahabad protests were being covered by social media users across Arab countries and Iran marked regional tensions. Image remixed by Digital Trends.

This post was written with data analytics contributions and technical consultations from Amir Rashidi, an Internet freedom researcher and activist.

Tensions Peak After A Kurdish Woman Falls to Her Death

Farinaz Khosrawani was a 25-year-old Kurdish chambermaid who fell off of a hotel room balcony on May 4 while allegedly escaping a sexual assault. The incident resulted in protests from Kurds in Mahabad, who set Hotel Tara on fire in reaction to her death. The situation later escalated to police using tear gas to disperse the angry crowds from the area in front of the hotel. The incident intensified when allegations of suspected foul play by a security official in Khosrawani’s death emerged. The city's Kurdish population demanded justice for committing the offense.

The tensions caused by this incident led to much social media coverage, often fueled by different biases and interests. Social media statistics indicated that one of the prominent groups in these discussions was Saudi Arabians, who called for solidarity between ethnic Kurds and Al Ahwazi Arabs, both significant minority groups inside of Iran, in opposing the Iranian state. To further support this, a Saudi cable that was recently published by the transparency group Wikileaks substantiated this application of social media by the Saudi government. The undated memo was sent from the Saudi Embassy in Tehran and suggested ways to publicly expose Iran’s social grievances through “the Internet, social media like Facebook and Twitter.”

The exiled opposition movement known as Mojahedin-e-Khalq (MEK) were another prominent voice on social media underlying the Iranian regime’s violence against protesters. Between May 4 and 20, these groups managed to create and carry out a social media strategy on Mahabad until it eventually started to fade.

The Mahabad trend underscored several social and political factors in play, and highlighted the degree to which Iran's social media discourse lags behind other countries due in large part to its censorship regime.

An Altered Discourse

Iranian mainstream media did not immediately speak about the incident. A flow of domestic publications about Mahabad tensions only emerged after the media became aware of the Mahabad social media trend, and their coverage suggested that the trend had originated from outside Iran. Iranian media referred to the incident as “a plot by anti-revolutionary groups” and warned Iranian users to be wary of such social media traps.

Conservative websites then took a more active role in describing the incident. This included a video from Hotel Tara’s CCTV camera which was circulated through Viber and conservative websites. The video showed Khosrawani entering a hotel room, with a man following her shortly thereafter. Her companion was said to be a private sector consultant, according to a hotel principal. The video suggested that these were arranged dates, and refuted earlier rumors about the role of a security official in the death. However, this footage was taken at a time of day different from the time that the incident occurred.

This active approach of the Iranian media partially soothed public anguish, but was not sufficient to terminate the social media disagreements that had already started. Nowhere is this more apparent than in tweets coming from Iranians in the Persian language, and from Saudi Arabian users in the Arabic language.

#العربیه #عربستان از تصویر 5 سال پیش بحرین رو به عنوان #شکنجه در #مهاباد استفاده کرد!! #عاصفة_الحزم pic.twitter.com/T1luEscS8G

— hamed safari (@safari_h) May 24, 2015

#Al #Arabyia has republished pictures from 5 years ago as evidence of torture on Shi’ite prisoners in Bahrain on the news of Mahabad tensions!

#عاجل هروب محافظ #مهاباد ومتظاهرين يحاصرون قائد الشرطة #إيران_تحترق #كردستان_تلتحق_بالأحواز_وتنتفض pic.twitter.com/OEyS91gIyZ

— مدمرهم (@Madmarham1) May 9, 2015

the #governor of #Mahabad fled and protesters besieged the police headquarters #iran_burning #Kurdistan_joinsAhwaz_inrising

These claims created a discourse on social media that was disconnected with the actual incident both in scope and content. The analysis of such discourse has become measurable through social media analytic tools. To this end, we tracked #مهاباد (Persian for #Mahabad) on Twitter and Instagram through Keyhole between May 4 (the day that Khosrawani passed away) and May 20. Keyhole is a social media analytic tool that enables real-time tracking of keywords and trends over Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook.

Mahabad Trend: A Look at the Data

Mahabad locals reportedly became aware of Khosrawani's death at Hotel Tara mainly through Viber groups that circulated the following message: “Kurdistan is not Isfahan. Our women are not alone. Please circulate. Thursday, outside Hotel Tara, we will demolish the venue. Let’s stay together.”

The main Viber message which was circulated among Mahabad locals on the evening of Wednesday, May 6. This screenshot was received from a local Viber user in Mahabad, who gave permission to republish the message under the condition of anonymity.

Mahabad did not soar on Twitter and Instagram until May 7, the same day that Hotel Tara was set aflame. Our keyword tracker #مهاباد (Mahabad) returned 1983 entries for Twitter and 111 for Instagram for the period of May 4-7. Among these was an unprecedented flow of Arabic tweets that started to appear on May 7 and amounted to 28% of the aggregate number of tweets bearing this hashtag. Some Arabic tags of these tweets implied the greater battle between Saudi Arabia and Iran. For instance, the term ‘اعاده الامل’ (Arabic for Revival of Hope) refers to a the campaign which a Saudi-led coalition initiated in April 2015, aimed at protecting Yemeni civilians and preventing Houthi fighters from operating. The campaign ostensibly replaced the Operation Decisive Storm (‘عاصفه الحزم’) in Yemen.

Another noteworthy phrase was #كردستان_تلتحق_بالأحواز_وتنتفض (Arabic for “Kurdistan raises and joins Al Ahwaz”). The phrase carries a historical reference to the autonomous emirate of Arabistan (currently Khuzestan) in southwestern Iran, which was forced to abide by the central state in 1925. The region has remained in a political flux between the central government and ethnic Arabs (Al Ahwazis), who claim autonomy. These posts occasionally included faux images of the 2009 Green Movement in Iran, displaying the streets of Tehran and police violence toward protesters.

عاجل عاجل: انتفاضة مهاباد تتسع لتشمل جميع المناطق الكردية والثوار يشكلون غرفة عمليات. #إيران_تشتعل نصرك يا الله pic.twitter.com/llWkIMg7KA

— ناصر الكعبي-الأحوازي (@nasserjabor) May 11, 2015

Breaking news: Mahabad rebellion expands to include all Kurdish areas and the rebels form am operations room. #Iran_isonFire. We ask Allah for victory.

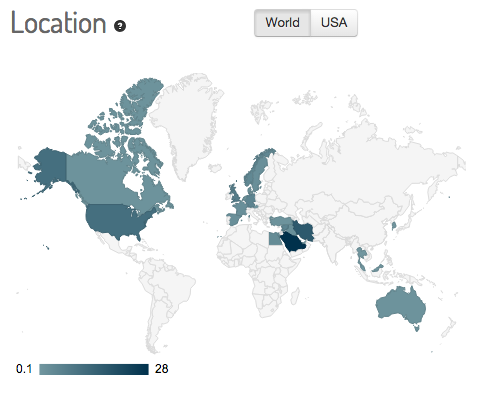

Saudi Arabia was not the only state in the region who reacted to the Mahabad incident. Given their relatively large Kurdish population, Syria, Iraq and Turkey were the other leading contributors. Five percent of the aggregate tweets and Instagram pictures originated in Syria or were associated with Syrian accounts. Respectively, Iraq and Turkey also generated 2% and 1% of the content.*

Aggregate stats from Twitter and Instagram for #مهاباد generated by Keyhole. May 4- 7

Percentage of Twitter and Instagram posts generated per country: Saudi Arabia (28%), Iran (17%), USA (11%) published most between May 4-7.

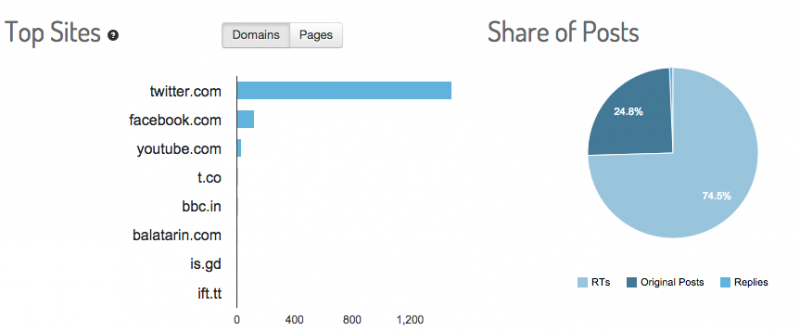

Top sites sharing content about Mahabad between May 4 and 7. The BBC and Balatarin, a Persian linksharing website, are among the top 5 sources.

The social media discourse over Mahabad tensions rapidly evolved in terms of content and influential disseminators. Between May 7 and May 8, Mahabad-tagged posts on Twitter and Instagram increased by 89%. In addition, Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA) and Mojahedin (news agency of People’s Mojahedin Organization of Iran, aka MEK) joined the debate. The former accused anti-revolutionary groups of feeding the rumors while the latter condemned the state for violating women’s and ethnic minority rights.

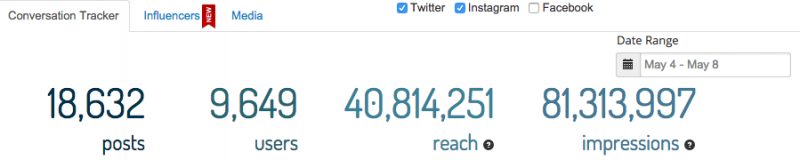

Twitter and Instagram stats for #مهاباد generated by Keyhole. May 4-8. The aggregate of 18,632 posts include 18,350 tweets and 282 pictures from Instagram.

MEK and Saudi-originated tweets rather aggressively addressed the issue of ethnic autonomy and called for separatist actions. However, tweets from Syria, Iraq and Turkey more sincerely demonstrated ethnic emotions and matters of honor and historical suffering of Kurdish population. By May 8, tweets and Instagram pictures from Syria had risen to 7%, Iraq’s to 3%, and Turkey’s to 2%.

Percentage of posts per country: Saudi Arabia (51%), USA (7%), Iran (6%), Syria (3%), France (2%), Germany (2%), Iraq (2%), Norway (1%), Sweden (1%), and Turkey (1%) posted the largest number of tweets and images between May 4-20.

The Mahabad trend started to diminish on Twitter about a week after the breakout of death news. However, the Twitter pulse was surprisingly revived after a brief unrest over the the championship of Iran soccer league that followed a game in Tabriz. A critical telecommunication disconnect occurred toward the end of the game. This facilitated dispersion of false rumors about the result of a parallel game that would have determined the league champion.

Enraged over the faux announcements, the crowd inflicted damage on the stadium property and was eventually dispersed by the police. Tabriz is the capital of East Azerbaijan province in northwestern Iran which is mainly populated by Azeri Turk ethnicity. Within a day, Mahabad was back on Twitter timeline. This time #Mahabad was tagged to the photos of unrest in Tabriz stadium. Tagged with #Iran_ignite, or #Iran_on_fire (#ایران_تشتعل), these images related the two incidents and concluded with an assumption of large scale unrest in the country. It went so far that the 2011 Yemeni Nobel Peace Prize laureate Tawakkol Karman, posted a tweet and alleged massive protests in 14 major cities of Iran. These photos are in fact images taken from the 2009 protests in Tehran and other Iranian cities.

Tabriz stadium after the announcement of Tractor not being the champion of the national league.

حرقت اليوم سيارة تابعة للحرس الثوري من قبل المتظاهرين الأكراد في #مهاباد #مهاباد_تنتفض #الاحواز_تنتفض #إيران_تشتعل pic.twitter.com/IeHFHa94HV

— دراسات إيرانية (@iranandarab) May 12, 2015

A car belonging to the Revolutionary Guards was burned today by Kurdish protestors in Mahabad. #Mahabad_revolts #Alahwaz_revolts #Iran_on_fire

الآيرانيون في مسيرات جماهيرية في اكثر من ١٤ مدينة يطالبون بإسقاط النظام ، الربيع الإيراني لن يطول انتظاره

— توكل كرمان (@TawakkolKarman) May 12, 2015

Iranians join massive rallies in more than 14 towns calling for the overthrow of the regime. We will not wait too long for the Iranian Spring

Between May 4 and 20, an aggregate of 127,834 posts about Mahabad populated Instagram (1,537 pictures) and Twitter (126,297 tweets), 51% of which had originated in Saudi Arabia. Moreover, only 13.3% of the aggregate number appeared to be original posts. The large percentage of reposting of the existing (Arabic) content underscores the lack of reliable news being delivered to the public. The absence of verified information and lack of awareness about the social media trend opened room for the proliferation of a state-influenced discourse. The situation escalated when the Twitter account of the Arabic-speaking Safa TV published an identification card that purportedly belonged to a member of Iran's Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). It was alleged that the ID belonged to the intelligence officer accused in Khosrawani’s death.

#المقاومة_الوطنية_الأحوازية.. تستفتح عملياتها العسكرية، بقتل ضابط #ايراني “محمد باقر غلامي”، ليلة البارحة في #مهاباد. pic.twitter.com/jffqG4Mnrc

— عاجل السعودية (@3ajel_ksa) May 13, 2015

#TheNational_Ahwazi_resistance launches its military operations by killing the #Iranian office ‘Mohammed Baqer Ghulami’ in #Mahabad last night

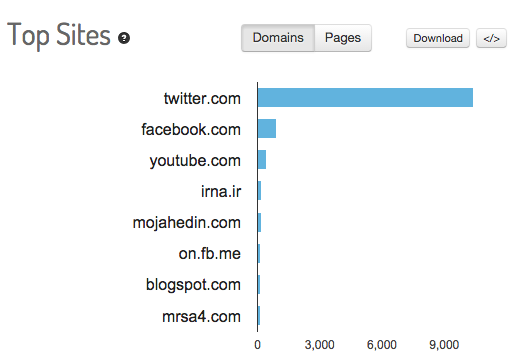

By May 20, the discourse had moved from the death of a young Kurdish women toward nationwide unrest (#Iran_ignite, #ایران_تشتعل). Saudi Arabia and Iran’s recent conflict over Yemen affairs surfaced through the overt tags of Operation Decisive Storm and the Revival of Hope campaign. Furthermore, MEK’s official website and Alriyadh Daily Press were leading the content dissemination about said unrest.

Twitter and Instagram stats for #مهاباد generated by Keyhole. May 4-20

How Iran Censorship Backfired on #Mahabad

Online campaigns are natural inheritors of social and political contexts, and Mahabad was no exception. The Mahabad incident underscored the challenges ethnic minorities face in Iran, particularly the Kurdish population, and their historic clashes with the central government. Mahabad is the traditional capital of Iranian Kurdistan and was briefly known as the Republic of Mahabad in 1946. The year 1946 was in fact detected among popular keywords in Arabic tweets posted about Mahabad. In addition, Kurdish populated areas also witnessed a brief period of unrest in 2005 following the death of a local Kurd activist by security forces in Mahabad. These sensitivities often go unacknowledged by national Persian media, a trend that has contributed to the climate of distrust in the central government.

Additionally, the Iranian judiciary has consistently failed to conduct fair trial standards for ethnic minority activists in detention. In March 2014, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran reported that 200 ethnic political activists, including Kurds, were detained or imprisoned. Many were reportedly tortured and/or convicted of association with armed opposition groups. The Islamic Republic not only has failed to effectively address these allegations, but it has also repeatedly censored news of ethnic minorities’ detention, harassment, or execution. Such practices often exacerbate the distrust of Kurds in the central government. Recent tensions in Mahabad were a reminder about said distrust.

Lastly, Khosrawani’s demise followed an earlier wave of acid attacks on several women in Isfahan in October 2014. These attacks were allegedly related to inappropriate Islamic attire. Despite local protests in Isfahan against vigilante violence, no suspect has been detained yet. Instead, the Islamic Republic resorted to detaining a photographer of the protests, and to deterring media to limit the reach of news. The initial silence of Persian media about Khosrawani’s death underscored the disproportionate news coverage of gender issues, in particular when matters of privacy and honor are involved.

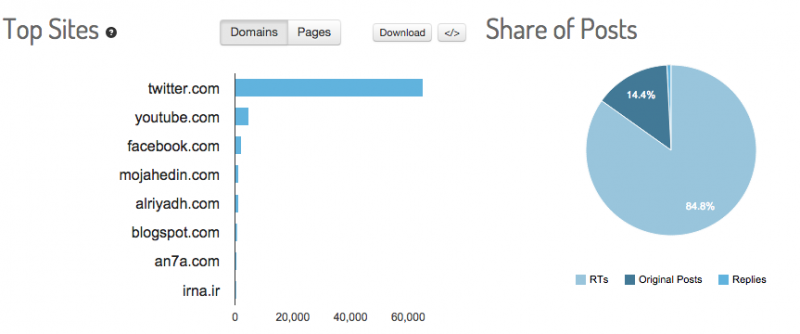

Share of posts on Twitter and top content sharing websites about Mahabad between May 4 and 20

#Iran_Ignite: A Self-Imposed Challenge of Censorship

Like other mediums, social networks can be both a means of accessing information as well as an opportunity to advocate or oppose certain points of view. Despite the fact that Iranian leaders are active on these networks, censorship prevails inside Iran on most of these platforms.

Yet Iranians often use social networks to not only express their concerns about social, political and cultural issues, but also to mobilize around a common cause. Examples include campaigns on acid attacks in Isfahan, Zarif’s allegation that there are “no political prisoners in Iran”, and Netanyahu’s comment on Iranians not wearing jeans. The main difference between these cases and Mahabad was the lack of public awareness about the Mahabad incident. Iranian media opted to remain quiet until the news went viral on social media. In the absence of credible information, Iranian users were late to respond to the incident over social media.

Relevant hashtags to Mahabad between May 4-20 refers to the recent regional disputes between Iran and Saudi Arabia over Yemen affairs.

A lack of state transparency about the incident also paved the way for groups such as MEK to take the lead in shaping the discourse and propagating an unrealistic narrative about the tensions. By the time Iranian media began reporting on Mahabad, this modified discourse was already being disseminated on social media.

In addition, the number of Persian publications covering the incident was insignificant compared to foreign outlets. Conservative Iranian news outlets such as Fars News and IRNA briefly contested the origin of Mahabad posts, but quickly pulled back on this coverage, while others continued to disseminate the news even after tensions diminished. The Islamic Republic’s restrictive policies on content production and dissemination, therefore, caused an effect that ran counter to its own national interests.

As adopting social media by world leaders, policy makers, and power institutions becomes commonplace, we will likely see more online rivalries similar to what occurred with #Mahabad. Social media renders a swift, low-cost online approach to disseminating content that is detrimental to the interests of adversaries. State censorship and filtering of social networks restrict the reach of credible information to Internet users at times when mobilizing toward a collective issue can make a meaningful difference. The case of Mahabad is only one example.

This post was written with data analytics contributions and technical consultations from Amir Rashidi, an Internet freedom researcher and activist.

* Twitter API search enables location detection based on multiple options, such as IP addresses, geo-tags and any information about location that a Twitter account may contain. Keyhole, being a commercial service, does not publicly reveal its specific methodology for detecting location. However, while doing this research, we compared a couple of smaller online campaigns to ensure the accuracy of the results. We concluded that Keyhole most likely detects location based on the three methods mentioned above. The same applies to the tweets coming from Turkey, Syria and Iraq.