WikiLeaks truck at Occupy Wall Street, 2011. Photo by David Shankbone via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 3.0)

Since the massive hack of the controversial Italian surveillance technology firm Hacking Team in July, journalists and human rights defenders have been combing through the 400GB of leaked data including internal memos, product documentation, sales records and emails from the company's servers.

Hacking Team is best known for its “Remote Control System” which the leaks confirm has been used by oppressive regimes from Ecuador to Egypt to Ethiopia to surveil and intimidate political opponents, journalists, and human rights advocates. Not surprisingly, it has been a hot topic within the Global Voices community.

A small group of Advox authors has been hard at work reading and parsing files day by day. A few weeks after the hack, WikiLeaks published more than one million searchable emails from the leaks. These have shed light on the modus operandi of the firm’s team, their communication with clients, and their regular analysis of the political dynamics in the Middle East and elsewhere. We were glad to see that WikiLeaks indexed and organized the emails into an easily searchable database — our research instantly became much faster and more efficient.

Many of the emails that we wanted to read contained attachments, mostly Microsoft Word documents with reports from meetings between Hacking Team staff, government agencies and third-party companies negotiating software purchases on behalf of governments. They looked harmless to us, and we wanted to see what they said. So we tried to open them. But then we ran into trouble.

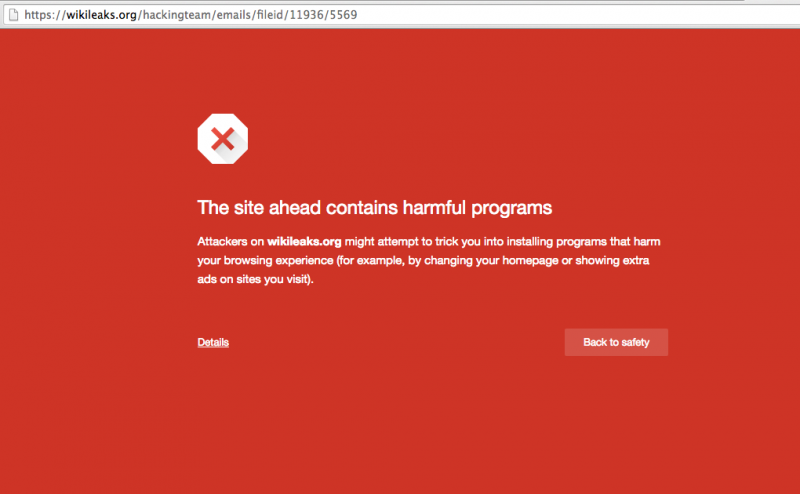

On several occasions, when using the Chrome browser, we saw the following warning when we selected an attachment to view:

Screenshot of Chrome malware warning on WikiLeaks, taken August 10, 2015.

The above warning came with this email, an internal message between Hacking Team staff, sent on July 25, 2014, concerning a contract with the Lebanese government.

Note: If you are reading this post on a browser other than Chrome, please take caution before clicking the email link. Below, you will find an alternative method for reading attachments such as this in a safe manner.

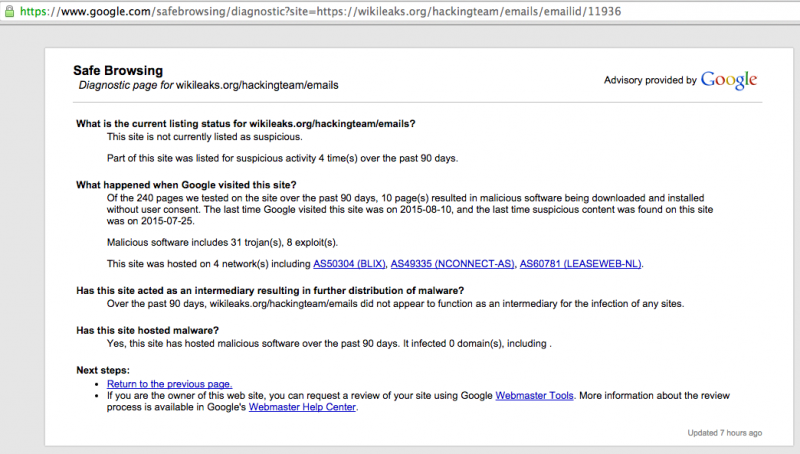

A search on Google Safe Browsing suggested the same:

Google safe browsing screenshot for Hacking Team leaks attachment from email ID: 11936. Taken Aug. 10, 2015.

Note: This is a great way to check the safety of any site on the Internet. Just type the search URL into your browser [https://www.google.com/safebrowsing/diagnostic?site=] and add the full URL of the site you want to test after “site=”.

We also contacted Google (operator of the Chrome browser) and confirmed that their security staff had indeed found malicious software in some of the email attachments posted on WikiLeaks.

The Google docs viewer workaround

We had to figure out a way to publish these stories and link to evidence without endangering ourselves or our readers. We did not want to publish links to these emails if they included malicious attachments. This felt like bad journalistic practice: It could put at risk any reader who clicked the attachment, and it could also deplete the trust that we have with our readers.

A colleague suggested that we review the attachments using Google Docs Viewer, which has a slightly hidden feature that makes it easy to view any online document via Google's processed HTML view.

This process is fairly straight forward:

1. Paste this URL in a new tab: https://docs.google.com/viewer?url=

2. Paste the address of the document you want to view online.

3. The document will appear in your browser, through the doc viewer. You can read its contents without actually downloading the file or putting your computer at risk.

So this is what we did. We opted to take screen captures of what we saw and to then turn these into a PDF which we hosted on our site. In the end, we were able to show readers all the evidence we needed to support our story, with none of the malware attached.

Is this normal?

The Guardian Project's Nathan Freitas, who has deep expertise in governments’ use of malicious software of this sort, told us that in a document dump as large as this one, it is common to find some malicious files. But he also noted that offering a clean version via “automated scrubbing, cleaning, or simply a “plain text” view of all documents should be provided, and is not hard to do.” He explained further:

Some people may still want to have access to the full original documents in order to see all trace metadata, history, etc in the documents themselves. That is how you can de-censor PDFs, or find hidden originator data in DOC files for instance, or look for modification artifacts in JPEGs. There is value to having the real, source files.

Clearly, for technical experts, having the original files from a system like this is valuable for research and information that can benefit the public interest. But for journalists, and any non-expert seeking merely to read the files, there could be some risk in the process.

Why is WikiLeaks hosting malicious files?

For us, the question still remains: Why is WikiLeaks hosting malicious files without giving users due warning? It turns out this is not the first time WikiLeaks has hosted malicious material on its site. In March 2015, tech blogger and systems administrator Josh Wieder noticed malware in the torrent of the Global Intelligence Files posted on WikiLeaks. He wrote:

…a significant number of the files included in the leak contain malicious files that are designed to, among other things, retrieve detailed information about the computers which have downloaded them and send them to a variety of remote systems.

In July, Wieder wrote an update post, describing how he had found malware not only in the torrent, but in curated content on WikiLeaks itself. The Register followed up on the story and verified that several of the files in the Stratfor leak indeed did contain malware in its usual seemingly innocuous form — PDFs, Excel files, links and even regular old image files.

The Register's Chris Williams wrote, “Unfortunately, no one appears to have had the time to scrub the five million Stratfor emails, which date back to 2001, clean of malware.”

We're glad that our community is not alone in confronting this problem, but we need help. We'd like WikiLeaks to respond to these concerns and publicly explain how they process leaked data before they load it to their site. Moving ahead, we hope the digital rights community and journalists working on these issues can work together to find a stronger, safer solution to this problem so that we can show evidence and encourage users to do their own research without putting anyone in danger.

4 comments