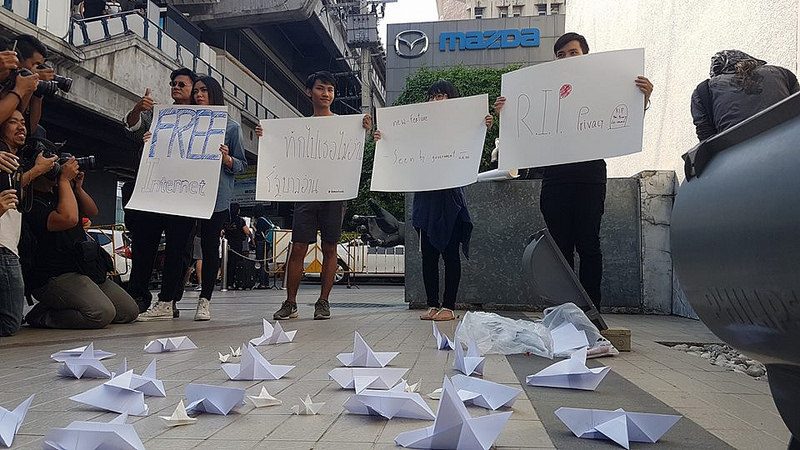

Activists stage a rare protest in Bangkok a few days after the passage of the revised Computer Crimes Act. Image from Prachatai, used with permission.

Thailand’s National Legislative Assembly voted unanimously on December 15 to pass an amendment to the 2007 Computer Crime Act. The new law, which will take effect after 180 days, has been criticized by several human rights groups for containing provisions that threaten to further undermine freedom of expression in Thailand.

The law was approved by a parliament whose members were appointed by the military, which took power in a coup in 2014. The junta said amending the law is necessary to combat cybercrimes but critics fear it is really intended to suppress dissent.

An online petition against the legislation led by the Thai Netizen Network has gathered over 370,000 signatures. The petition cited some of the provisions in the law which could be used by authorities to intimidate the media and even ordinary Internet users.

For example, section 14 criminalizes the sending of “false computer data” or Internet content that damages “the maintenance of national security, public security, national economic security or public infrastructure serving public interest or cause panic in the public.”

The Bangkok Post newspaper is suspicious about this provision:

There is no clear definition of what acts may be construed as being in breach of this section. Will criticizing the government's megaprojects qualify as damage to national security or public infrastructure? How about opinions about the state of the country's economy?

#Thailand junta pushes #cyber law that could censor & prosecute human rights reporting as “false/distorted” information or security threat. pic.twitter.com/TFFu5RrvIU

— Sunai (@sunaibkk) December 15, 2016

Meanwhile, section 15 could lead to self-censorship on the part of local Internet Service Providers because it penalizes all parties that “cooperate [in spreading] false computer data”. This section also allows officials to obtain Internet traffic data from ISPs without court approval. This could also lead to more costs that will negatively affect both business and consumers.

Section 16 criminalizes the possession of information that the court has ordered to be destroyed. This could hamper the work of researchers and journalists. Some are worried that the computer cache or Internet browsing history of ordinary netizens can be retrieved by authorities to monitor if they are storing banned content.

Section 18 allows authorities to access encrypted data. It is not clear how this would be carried out in practice.

Section 20 empowers a committee appointed by the government to monitor and even order the removal of dangerous Internet content. The Bangkok Post is referring to this provision when it published an editorial criticizing the amended law:

The draft amendment's most serious shortcoming is in its giving too much power for state authorities to make their own judgement whether certain actions may be deemed in violation of the law.

Even though the law is not yet in effect, authorities are already aggressively blocking ‘harmful’ Internet content, especially those deemed to be disrespectful to the monarchy. Thailand implements a strict lese majeste (anti-royal insult) law which some activists believe is being abused by the junta to harass and detain its critics. According to the government, it shut down 1,370 websites in October for violating the lese majeste law. This is massive compared to the 1,237 websites shut down by the government in the past five years.

Revised computer crime act – cartoon of the day – @PravitR @Reaproy @KrisKoles pic.twitter.com/5RRt3MAbm7

— stephff cartoonist (@stephffart) December 20, 2016

Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha defended the law by insisting that it will not violate civil liberties. Some businesses also welcomed the passage of the law which they believe will protect intellectual property rights and spur the development of the digital economy.

But protests were also organized a few days after the law was approved by the parliament. The online activist group Citizens Against Single Gateway claimed that it hacked several government websites.

When the government will not listen to the wishes of the people, the people are angry. #กลุ่มนิรนาม #Anonymous #Thailand #พรบคอม #พรบไซเบอร์ pic.twitter.com/7t4jeO1wAe

— Anonymous (@blackplans) December 17, 2016

The #Thai gov wants to #police the #internet, #Thai police can't guard their own data from #Anonymous, is your data safe with them? #พรบคอม pic.twitter.com/S6c8jJxjHo

— Anonymous (@blackplans) December 16, 2016

Thai Netizen Network acknowledged the sentiment of Anonymous but it also urged the group to consider the protection of data by ordinary Internet users:

Thx for support, #Anonymous. U made ur point. Further hack may harm Thai citizens more than Junta. Pls u consider avoid citizen data? Thx :)

— เครือข่ายพลเมืองเน็ต (@thainetizen) December 17, 2016

Several international groups such as the United Nations Human Rights Office in Asia and the Committee to Protect Journalists also issued statements expressing concern about the passage of the law.

This video by The Nation newspaper summarizes the critique of media groups about the vague and problematic provisions of the law:

1 comment