Vladimir Putin meets the top editors of major Russian news outlets. Most of them are now either directly controlled by the state or owned by one of its loyal oligarchs // kremlin.ru under CC2.0

On May 20, 2019, the management of Kommersant, one of post-Soviet Russia’s oldest and most respected business newspapers, forced its two star reporters, Ivan Safronov and Maxim Ivanov, to resign.

The incident was triggered by an April 2019 article that Safronov and Ivanov co-wrote, along with three other staff reporters, about the possible resignation of Valentina Matviyenko, the speaker of Russia's upper chamber of parliament, the Council of the Federation.

Citing anonymous sources, the article alleged that Matviyenko, a veteran politician who was the governor of St. Petersburg before taking the job in the parliament, was considering another top government position.

This was nothing out of the ordinary: well-respected publications in Russia often publish articles based on nothing but anonymous sources, as the country’s notoriously secretive ruling circles are reluctant to go on record about even the most trivial matters of bureaucratic musical chairs.

Sometimes these anonymous scoops do play out, but this particular one did not. One month has gone by since the story ran and Matviyenko has still not resigned. Perhaps the article spooked her plans, or perhaps it was simply wrong.

What came next was shocking to many, though not unprecedented: both reporters were forced to resign.

Maxim Ivanov announced the news on his Facebook page:

С завтрашнего дня я больше не работаю в ИД «Коммерсантъ».

Если без лирики: уход из Ъ оформлен по соглашению сторон, а решение о необходимости прекратить трудовые отношения принято акционером ИД. Поводом стала заметка «Спикеров делать из этих людей», в которой сказано о возможном уходе Валентины Матвиенко с поста председателя Совета федерации.

As of today, I’m no longer employed at the Kommersant publishing house. To avoid waxing lyrical: formally, my resignation from Kommersant is a mutual agreement between parties, but the decision to terminate my employment was made by the publishing house’s stakeholder. The reason is an article […] about the alleged resignation of Valentina Matviyenko from the position of the speaker of the Council of the Federation.

Kommersant has only one true “stakeholder” in Alisher Usmanov, one of the wealthiest people in the world, and the owner of a vast media empire which includes Kommersant, Megafon, one of the top four mobile providers in the country, and the Mail.Ru Group which owns stakes in two of the most popular social networks in the Russian-speaking world, Vkontakte and Odnoklassniki.

Kommersant is a tiny speck among Usmanov’s other assets but its political coverage seems to have caused him significant problems. In March this year, another Kommersant reporter, Maria Karpenko, was forced to resign over the Telegram channel she administered.

Several former and current employees told Runet Echo that Usmanov’s interference in the newspaper’s editorial affairs has been constant over the years, whenever he felt the coverage threatened his business interests or angered his patrons in the Kremlin.

In 2011, Maxim Kovalsky, the editor of Kommersant’s political magazine Vlast (Power) was fired for the magazine’s issue covering the mass fraud during the parliamentary elections.

Печально, что к таким чисткам в СМИ начинаешь привыкать. Газета.ру, Лента, Деловой Петербург, теперь Коммерсант. Это список можно продолжать. Крупных независимых СМИ все меньше.

— Andrey Pivovarov (@brewerov) 20 мая 2019 г.

It’s sad that we’re getting used to these purges in the media. Gazeta.ru, Lenta.ru, Delovoy Peterburg, now Kommersant. The list could go on. There are fewer and fewer large independent media outlets.

In an interview with Vedomosti, a competing business newspaper, Kommersant editor-in-chief Vladimir Zhelonkin said that Ivanov and Safronov had to resign because their article did not comply with editorial standards. He did not specify which standards exactly and skirted around the fact that he, as the top editor, had run the story on the newspaper's front page story when it came out. He also denied the allegations of Usmanov's involvement.

Just hours after Ivanov and Safronov were made to leave, the entire politics desk of Kommersant, several dozen people in total, resigned in protest and in solidarity with their colleagues.

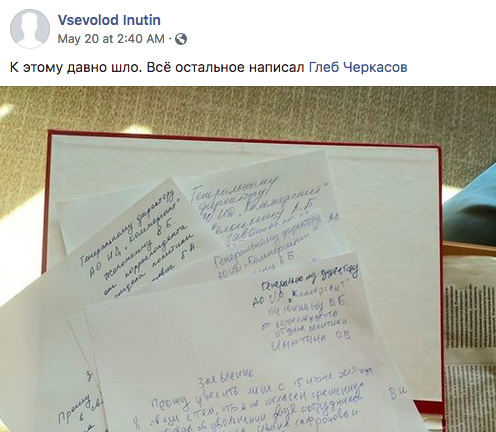

One of the reporters, Vsevolod Inyutin, posted on his Facebook page a stack of signed notices saying: “I hereby resign from my position due to my disagreement with the stakeholder’s decision to dismiss two employees of the politics desk, Ivan Safronov and Maxim Ivanov.”

Screen capture of Vsevolod Inutin Facebook post.

К этому давно шло. Всё остальное написал Глеб Черкасов

It has been brewing for quite a while. Gleb Cherkasov [editor of Kommersant's politics desk] said the rest.

Crippled by mass resignations, Kommersant seemed unable to cover a crisis in its own ranks:

Just got Kommersant newspaper's daily “Most important stories of the day” newsletter in my inbox

Guess what it doesn't mention https://t.co/l7Wg7E8f78

— Polina Ivanova (@polinaivanovva) 20 мая 2019 г.

StalinGulag, a previously anonymous political blogger who became the focus of media attention when his true identity was revealed by investigative reporters, wondered why a newspaper in today’s Russia even needed a politics desk:

“The publication's shareholders decided wisely — ‘Why would you need the political desk in Kommersant newspaper if there's no politics in the country,'” quipped @StalinGulag, a prominent anti-Kremlin blogger. Our latest on the @kommersant uproarhttps://t.co/rvyGYEbBRq

— Anna Smolchenko (@Annaafp) 20 мая 2019 г.

However, not all were sympathetic to Kommersant reporters’ plight.

On Telegram, some have wagered that the fired reporters’ public posturing was part of an attempt to promote the news outlet they were launching.

Meduza editor (and former RuNet Echo editor) Kevin Rothrock tweeted about the rumors:

Heard the rumors that the former politics desk from @kommersant is developing their own new media outlet? @sssmirnov says it’s a bullshit story planted to generate sympathy for the newspaper’s management. https://t.co/JXpBqMtrh1

— Kevin Rothrock (@KevinRothrock) 21 мая 2019 г.

Alexey Navalny, a prominent opposition politician, tweeted:

Дело, конечно, прошлое, но когда Усманов подал меня в суд за фразу «Усманов проводит цензуру в газете «Коммерсант» никто из журналистов Ъ (прошлых и нынешних)не выступил свидетелем в мою пользу. Все струсили. pic.twitter.com/Omy5MkWsBN

— Alexey Navalny (@navalny) 20 мая 2019 г.

It’s all water under the bridge, of course, but when Usmanov sued me for saying that “Usmanov censors the Kommersant newspaper,” none of its reporters (former or current) stepped forward to be my witness. They all chickened out.

Navalny then wrote a lengthy post on his website accusing Kommersant’s reporters and editors of cowardice and acquiescence, and while still offering them legal support. He also called everyone who still hasn’t resigned a strikebreaker who should be ostracized.

But alongside Navalny’s public spat with journalists — one of many in his political career — there were others who echoed his statements.

RBC, another business news outlet competing with Kommersant and facing many of the same problems — its top editors were forced to step down after an investigation of Vladimir Putin’s wealth — wrote about the historical roots of today’s political crisis in Russian media:

Looking at the Kommersant scandal, Andrei Kolesnikov has some interesting thoughts about the “sham economics” of contemporary Russian journalism. https://t.co/MwJtW1dvpZ pic.twitter.com/EV2iIPASYu

— Kevin Rothrock (@KevinRothrock) 22 мая 2019 г.

Given that Russia’s top publications are either directly state-owned or belong to oligarchs loyal to the Kremlin, it’s unlikely that the crisis will be resolved anytime soon.