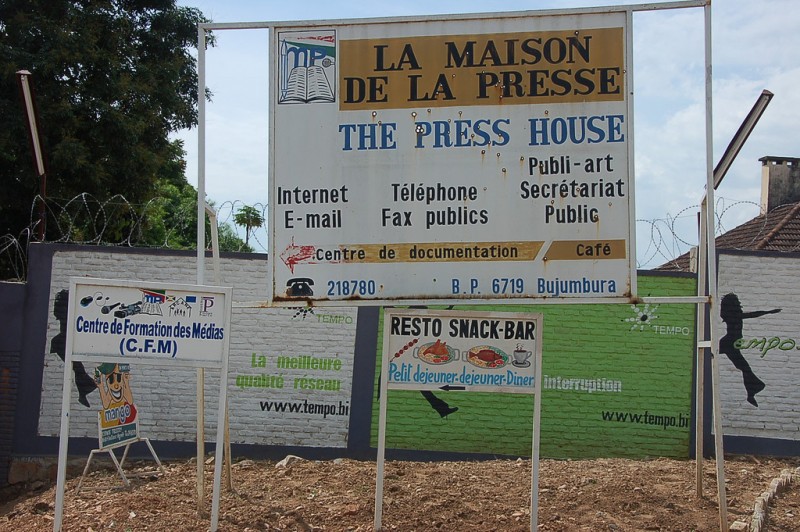

The Press House in Bujumbura, from which independent radios were blocked access. 19 May 2010. Photo by DW Akademie [1] – Africa via Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0 [2].

Four journalists — Agnès Ndirubusa, Christine Kamikazi, Térence Mpozenzi and Egide Harerimana — were charged with attempting to undermine state security and were sentenced in January 2020.

The four, who all work with Iwacu newspaper, adamantly reject the charges. They now await [3] an appeal decision on their prison sentence, after their hearing on May 6.

Antoine Kaburahe, Iwacu founder who now lives in exile, wrote [4]:

(1)Urgent/ Fin de l'audience à Bubanza. La défense de @iwacuinfo [5] est satisfaite.Les accusations contre les journalistes ne tiennent pas.Les journalistes ne faisaient que leur métier:informer.Quel soulagement! L’affaire a été mise en délibérée, verdict dans max 30 jours.Courage! pic.twitter.com/PYRXSJOhIp [6]

— KABURAHE (@AntoineKaburahe) May 6, 2020 [7]

Breaking: End of court hearing in Bubanza. Iwacu’s defence is satisfied. The accusations against the journalists do not hold up. The journalists were only doing their job: reporting. What a relief! The case is under consideration, verdict in max 30 days. Stay strong!

Detained for reporting

On October 22, Burundian security forces battled with an armed [8] anti-government group — reportedly [9] RED-Tabara, based in the Democratic Republic of Congo — around the Kibira forest border area. Armed groups have often used this area to move through the region. In the battle, 14 insurgents were said to be killed, while security forces suffered [10] about 10 casualties.

Later that day, police detained [11] the four Iwacu journalists and their driver, Adolphe Masabarakiza, when they went to report [12] at the Musigati commune, Bubanza province, to speak to people who had fled the fighting. At first, they were detained [13] without charge, and Christine Kamikazi was reportedly hit when arrested. Police confiscated their phones and materials and the intelligence services demanded account passwords in order to search their phones.

The journalists were then transferred [14] to other cells with deplorable conditions. On October 26, in Bubanza province, they were finally charged [15] with “complicity in threatening state security.” On October 31, the public prosecutor confirmed [16] this and accused them of having information on the insurgents’ attack.

Various organizations promptly called [17] for their release, including Human Rights Watch, International Federation of Journalists, Olucome [18], African [19] Journalists’ Federation and the Association Burundaise des Radiodiffuseurs [20]. However, the National Communications Council said [21] at the time that it could not discuss the matter. Iwacu criticized [22] this reaction, recalling that they were first held without charge and that the council is supposed to support journalists.

Many people expressed support [23] online and signed a petition [24]. International media [25] discussed [26] it as a threat to press freedom, while Iwacu continues to follow [27] the situation [28] closely.

Journalist Esdras Ndikumana tweeted [29]:

Burundi: 4 journalistes de Iwacu (et leur chauffeur) accusés de “complicité d’atteinte à la sécurité intérieure de l’état” pour avoir couvert une incursion rebelle dans Bubanza croupissent dans la prison de cette province (Dessin de Yaga) pic.twitter.com/CmRw0BPwHY [30]

— esdras ndikumana (@rutwesdras) October 31, 2019 [31]

Burundi: 4 Iwacu journalists (and their driver) accused of “complicity in threatening the interior security of the state” for having covered a rebel incursion in Bubanza languish in the this province’s prisons (Drawing by Yaga)

Court hearing

After appealing the decision on their detention, the date [32] for their court hearing was set for November 18, To their surprise, they were summoned [33] on November 11, to appear before judges for questioning — but without lawyers. They refused to answer without legal assistance, asking why their lawyers had not been informed beforehand, and then returned to detention, to be heard on November 18.

On November 20, the decision came that the four journalists [34] would remain in detention, but the driver was provisionally released. The prosecution originally called [35] for a 15-year prison sentence [36].

President Pierre Nkurunziza said [37] during a press conference on December 26 that he wanted a fair trial but he could only intervene as a last resort, even though he could use his power to grant a presidential pardon.

Sentencing

On January 30, in Bubanza [38], the four journalists were sentenced [39] to two and a half years in prison and a fine of a million francs each ($521 United States dollars) under article 16 of the Penal Code [38], while the driver was acquitted.

The prosecution could not prove any actual link or contact with the rebels, so the charge was changed to “impossible attempt at the complicity in undermining state security,” that is — that they intended to threaten state security but it was not possible.

Iwacu pointed [40] out that the reporters went to the area after authorities had publicly mentioned the incident, were accredited, and there were no restrictions [41] on the area.

The key element used [9] as evidence against the journalists was a WhatsApp message sent by one of the reporters to a friend, which said they were going to “help the rebels.” They argued it was clearly a dry joke — the government has often conflated critics, political opponents, and armed groups to justify generalized crackdowns. [42] But the text was taken literally as evidence against them.

Reporters Without Borders (RSF) said [39] the journalists should be able to report on sensitive topics without fear of reprisals [43], particularly ahead of Burundi's May 20 election. They made [44] a petition [45] calling for their release, which had almost 7,000 signatures in early May.

European Union deputies [46], the European Parliament [47], and UN human rights experts are among those who called [48] for their release.

Appeal

On February 20, the journalists appealed [49], questioning the quality of the legal process, including the change to the original charge without proper notification. On May 6, the journalists appeared [50] at an appeal [51] hearing [52], after approximately six months in jail.

Responding to the accusation based on the WhatsApp message, the defense noted that in another message, one journalist said the rebels were coming to “threaten the peace.” RFI quoted [51] their defense lawyer, Clément Retirakiza, saying there was an absence of evidence against them, and they wanted to show it was a purely professional trip.

Iwacu has long been an independent [53] voice that criticizes [54] politicized violence — it is one of the last independent media outlets following the 2015 crackdown [55].

A history of violence against journalists

After controversial 2015 elections — in which Nkurunziza returned for a third term that many argued as unconstitutional — there was a failed putsch. The media environment quickly deteriorated. [56] Several radios stations — the most relied upon for information in Burundi — were closed [57] and some were attacked. Dozens of journalists fled and some suffered torture, such as Esdras [58] Ndikumana [59].

Numerous journalists have also experienced violence [60] from security forces, particularly when reporting on topics deemed “sensitive” by the state. In late 2015, cameraman Christophe Nkezabahizi was killed [61] by police along with three family members, in an operation against protests after the contentious election.

In July 2016, Jean Bigirimana was forcibly disappeared [62], reportedly arrested by intelligence services (SNR), with a limited police investigation.

This year, on January 16, reporter Blaise-Pascal Kararumiye with Radio Isanganiro (Meeting Point Radio) was arrested [63] following a report on local government finances. On April 28, journalist [64] Jackson Bahati was hit by a police officer while reporting.

International media have not been spared, with BBC and VOA banned [65] in 2019. RSF ranked [66] Burundi 160 of 180 countries for press freedom — down 15 from 2015.