[1]

[1]Rappler CEO Maria Ressa (center), former Rappler writer Reynaldo Santos Jr. (left), and lawyer Theodore Te (right) held a press conference after their hearing at the Manila Regional Trial Court. Photo by Kodao Productions, a content partner of Global Voices.

A Manila court convicted [2] one of the Philippines’ leading journalists on charges of cyber libel in a case widely seen as the latest attack on dissenting voices and press freedoms in the country.

Manila Regional Trial Court Branch 46 Judge Rainelda Estacio-Montesa sentenced news website Rappler’s chief executive editor Maria Ressa and former reporter Reynaldo Santos Jr. to 6 months and 1 day up to 6 years in jail and ordered them each to pay P400,000 (about US$8,000) for moral and exemplary damages on June 15.

Ressa and Santos are the first journalists in the Philippines to be found guilty of cyber libel since the law was passed in 2012. They were allowed to post bail pending appeal under the bond they paid in 2019, which cost 100,000 pesos (2,000 US dollars) each.

Rappler, an independent website of international renown has been targeted by the administration of President Rodrigo Duterte. The court, however, found Rappler itself to have no liability in the cyber libel case.

Targeting Rappler

Press freedom advocates in the Philippines and across the world swiftly decried Ressa’s conviction as part of the Duterte administration’s campaign to terrorize and intimidate journalists.

The case against Ressa and Rappler was filed in 2017 by businessman Wilfredo Keng [3] over a 2012 Rappler story covering his alleged links to Supreme Court Chief Justice Renato Corona, who was being impeached [4] on corruption charges at the time.

Keng’s case was initially dismissed in 2017 because it was beyond the statute of limitations. Moreover, the article itself was published four months before the cybercrime law was enacted.

But the case was subsequently readmitted by the Philippine justice department, which extended the period of liability for cyber libel claims from one year to 12 years and argued the article was covered by the law because it was ‘republished’ in February 2014, when Rappler updated it.

While Duterte [5] and his spokesmen [6] deny any links to the cyber libel case, Rappler has been on the receiving end of regular ire from the president and his allies for actively investigating and exposing the administration's bloody war on drugs, social media manipulation and corruption.

Rappler reporters were banned [7] from covering presidential press briefings in 2018, for what Duterte characterized as “twisted reporting” during a presidential address.

Pro-Duterte trolls deride Rappler as a peddler [8] of “fake news” and hurl invective at its reporters.

The cyber libel case is but the first in a total of 8 active legal cases [9] against Ressa and Rappler which include another libel case and tax violation allegations. All were filed after Duterte came to power in 2016.

The Duterte government moved to shut down [10] Rappler in January 2018, claiming that it violated laws on non-foreign ownership of media outlets — a claim that is demonstrably false.

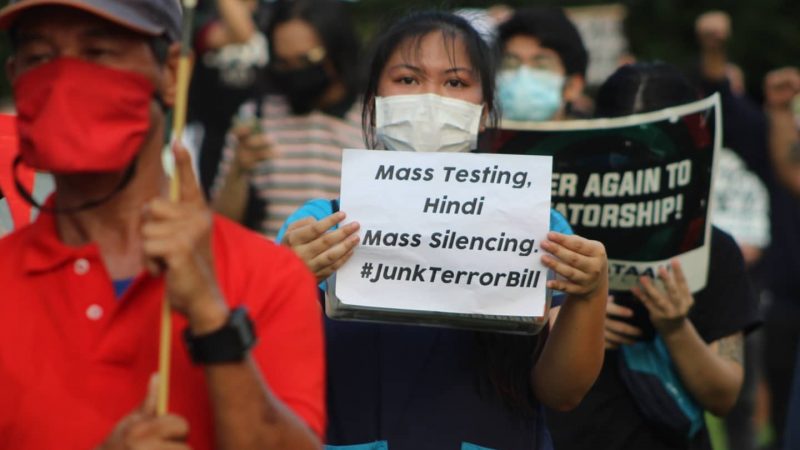

[11]

[11]A protester calls for ‘mass testing, not mass silencing’ at a rally held on June 4, 2020, the day the Philippine Congress passed the anti-terror bill. Photo by Kodao Productions, a content partner of Global Voices

Curtailing dissent

The College of Mass Communication of the University of the Philippines (UP), the country’s premier state university, condemned [12] the decision as a dangerous precedent that gives authorities the power to prosecute anyone for online content published within the past decade:

The State can prosecute even after ten, twelve or more years after publication or posting. It is a concept of eternal threat of punishment without any limit in time and cyberspace.

The National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP) said [13] the charges that Rappler faces is only the latest in “a chain of media repression that has seen the forced shutdown of broadcast network ABS-CBN and a spike in threats and harassment of journalists, all because the most powerful man in the land abhors criticism and dissent.’’

The government forced the country’s largest television network, privately-owned ABS-CBN, off air [14] last May after the pro-Duterte congress refused to renew the station’s broadcasting license.

Growing persecution of media comes against the backdrop of an anti-terror bill [15] passed by the legislature that allows the president to create an anti-terrorism council vested with powers to designate individuals and groups as “terrorists.”

That designation in turn allows warrantless arrests and 24 days of detention without court charges, among other draconian provisions.

Authorities have brazenly denied [16] the bill threatens freedom in the country.

[17]

[17]AERIAL SHOT: 5,000 human rights advocates and activists observe physical distancing as they commemorate Philippine Independence Day and hold a ‘Grand Mañanita’ against the Duterte government's Anti-Terrorism Bill today, June 12, on University Avenue, University of the Philippines- Diliman, Quezon City. Photo and caption by Kodao Productions, a content partner of Global Voices

Holding the line

At a press conference after her court hearing, Ressa vowed [18] to hold the line:

Freedom of the press is the foundation of every single right you have as a Filipino citizen. If we can’t hold power to account, we can’t do anything.

A few days before Ressa’s conviction, thousands defied [19] the lockdown to join anti-terror bill protests in Manilla despite threats of violence from the police.

Protesters ironically described their demonstration as a “mañanita” — the word that Police General Debold Sinas, a Duterte ally, used to justify [20] his birthday party celebration, which took place amidst severe restrictions on gatherings.

Double standards for Duterte allies and the weaponization of laws against critics were a constant theme in tweets that used the #DefendPressFreedom hashtag in response to the Ressa case.

Standing up for @mariaressa [21] Ray and @rapplerdotcom [22] not because I think they are above the law but because their case shows how the Duterte govt twists the law so it becomes a weapon against civil liberties. #DefendPressFreedom [23] #HoldTheLine [24]

— inday espina varona (@indayevarona) June 14, 2020 [25]

If they can do it to ABS-CBN and Maria Ressa (Rappler), they can do it to other media organisations and to anyone.#DefendPressFreedom [23] pic.twitter.com/50IIJxbYaZ [26]

— #SaveLumadSchools (@maykamaykaba) June 15, 2020 [27]

LOOK: Timeline on Maria Ressa's Cyber Libel Case

Today, June 15, the Manila Trial Court convicts Rappler CEO and executive editor Maria Ressa and former researcher-writer Rey Santos Jr of cyber libel.#DefendPressFreedom [23] #StandWithRappler [28] pic.twitter.com/68E0rgnPQz [29]— CEGP (@CEGPhils) June 15, 2020 [30]