Image courtesy Giovana Fleck

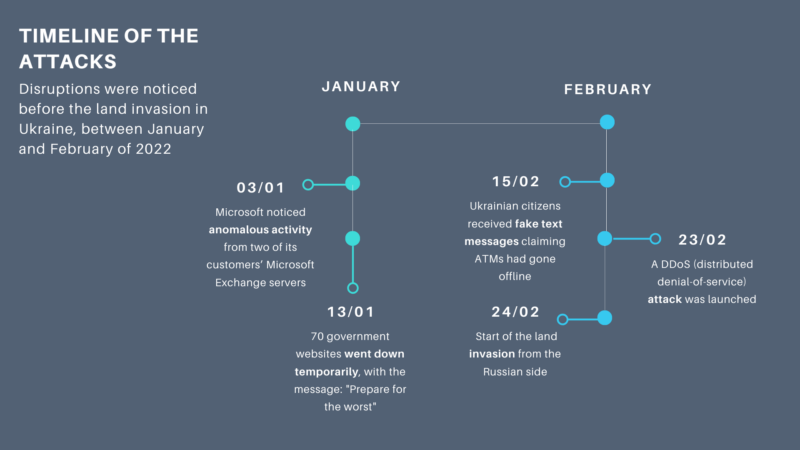

On January 3, 2022, Microsoft noticed unusual activity from two Microsoft Exchange servers: sending a large amount of data to IP addresses. Investigation revealed that the attackers, later identified as Russian hackers, used a vulnerability [1] in Microsoft to steal the entire contents of several user mailboxes worldwide, including in Ukraine, the US, and Australia. This was the first of a series of cyber attacks on Ukraine, including taking down government [2] websites and putting out threatening [2] messages, sending Ukrainians to withdraw [3] cash from ATMs, DDoS [4] attacks on banking, bomb [5] threats to schools, and even a malware wiper [6] that would erase all data in a network.

Russia never acknowledged these attacks [4]; but there is convincing evidence that Moscow either hires or encourages Russian hackers [7] to conduct attacks.

Russia has previously been implicated in cyber attacks in Ukraine, Estonia, Georgia, and the US. In 2014, four days before the Ukrainian parliamentary elections [8], malware was installed on the Ukrainian central election system, which then portrayed a pro-Russia candidate as a winner. This malware compromised and deleted critical files, and made the vote-tallying system inoperable. After the polls closed, the Ukrainian Central Election Commission faced DDoS attacks that disabled their network. As a result, they were unable to announce results for two hours. During these two hours, the Russian media announced that the candidate they supported had won [9] the election with 37 percent of the votes.

In 2015, Russian cyber troops launched [10] remote malware attacks against Ukraine. A malware known as BlackEnergy [11] targeted individuals’ emails in different energy companies. Once these individuals clicked on the attached malware, they activated KillDisk destructive malware which wipes out parts of the computers’ hard drives and prevents systems from rebooting. This led to power outages in Ukraine. Hackers simultaneously launched a TDoS (Telephony Denial of Service [12]) attack to prevent citizens from calling the electricity help centre to report any loss of power. This double attack caused a severe electricity blackout in Ukraine that affected more than 225,000 citizens. The incident [13] is considered to be the first remote public infrastructure attack using cyberweapons.

A tested strategy: Cyber attacks on Russia's neighbours

In 2007, during a dispute between Russia and Estonia following Tallinn's decision to relocate one of the Soviet World War II war memorials [14] from its original place, Russian cyber troops took down [15] the Estonian state’s banking and public administration systems after hijacking and harnessing a million computers worldwide in an operation called BotNet [16]. It is estimated that Russia used more than one million [17] computers from 70 different countries in this attack. Estonia requested [18] help from NATO under Article V [19] on collective defense, yet NATO was not able to offer support at that time, a situation that brought up the issue of cyberattacks as requiring the organization's collective defense. Later, the alliance adopted [18] the strategic concept [20] to “prevent, detect, defend against and recover from cyber-attacks, including using the NATO planning process to enhance and coordinate national cyber-defense capabilities, bringing all NATO bodies under centralized cyber protection, and better integrating NATO cyber awareness, warning and response with member nations.”

In August 2008, Russia and Georgia engaged in an armed conflict over South Ossetia, a territory that seceded from Georgia. While conducting military operations, Russia oversaw DDoS attacks [15] against numerous Georgian websites that severely affected communication and financial services. In response, the National Bank of Georgia on 9 August ordered [15] all banks to stop offering electronic services. Unfortunately, the Georgian physical infrastructure ran through Russia and Azerbaijan (in addition to a single fibre optic cable to Turkey). During the escalation of the conflict, Russian troops locked the optic cables of international telephone traffic [21] and seized both cellular and primary international telephone traffic. This lock caused an overload on the rest of the channels used by civilians and non-governmental organizations.

With the degradation of its communication channels, the Georgian government decided to censor Russian news and communication, and to filter Russian IP addresses [22] from their network to stop DDoS attacks. This reduced DDoS attacks temporarily, but then hackers started to mask their IP addresses and targeted Georgian services on foreign hosts. For example, Russian hackers attacked US-based servers with DDoS after the Georgian government migrated their server to a private web server in Atlanta [22].

After the Russian DDoS cyber attack, many pro-Georgia hackers [15]started counter-attacks against Russian servers, including a few Russian media sites. But with Russian websites, communication, and news blocked, Georgian citizens soon drowned in an information blackout. The media censoring and internet filtering created panic and helped spread rumors and disinformation about a Russian victory [21].

The Georgian government was unable to debunk false news or to connect with its citizens. The state of confusion and suspicion had a significant effect on morale, which reflected on the battlefield [22].

In this war, Russia achieved their victory by controlling the streams, the internet, and the narrative by disabling government services, websites, financial servers and denying Georgian citizens access to information.

Lessons for Ukraine

This holds lessons for Ukraine’s current challenges. In Ukraine, once Russian cyberattacks started in February 2022, an anonymous pro-Ukraine hacking collective announced that it had targeted [23] Russian TV channels to show pro-Ukrainian messages, while a Telegram channel [6]had been formed with thousands of members fighting online for Ukraine.

Unlike Georgia in 2008, Ukraine is backed [24] electronically by NATO and its neighbours. After Russia moved its troops toward Kyiv, NATO signed [2] an agreement with Ukraine to enhance its cyber capabilities and give it access to the alliance’s malware information sharing platform. The White House also offered [25] the Ukrainian government cyber support. Elon Musk offered [26] his satellite broadband service, Starlink, to run government servers. Additionally, the European Union formed a cyber rapid-response team [4] (CRRT); headed by Lithuania, this team includes 12 experts [27] from Lithuania, Croatia, Poland, Estonia, Romania, and the Netherlands, from private and government entities [24]. Romania also launched [28] a partnership to provide pro bono technical support and threat intelligence to Ukraine’s government, businesses and citizens.

Despite attempts by Ukraine to return the attack, it is difficult to assess their success. One possible indication could be dated to May 9, when hackers interrupted Putin's speech [29] on TV during the celebration of Victory Day. On that day, Russia smart TV users’ and online viewer saw the names of their TV programmes changed [30] to “The blood of thousands of Ukrainians and hundreds of their children is on your hands. TV and the authorities lie. No to war.”

A timeline showing major events in the Russian attack on Ukrainian internet. Image courtesy Giovana Fleck.

Surprisingly, despite their capacities, Russian hackers have only caused moderate harm to Ukraine’s digital infrastructure. Both parties have made mistakes similar to the ones experienced in Georgia. Putin recently blocked [31] all Western media websites and social media like Facebook, Instagram and Twitter, to saturate Russian citizens with Russian discourse. Russian security services have also started to randomly search [32] citizens’ mobiles in the streets, looking for anti-war posts, photos, videos, or messages.

At the same time, the EU decided to block [33] Russian propaganda arms like Sputnik and Russia Today. The Ukrainian president also banned [34]on March 20 eleven left-wing opposition parties accused of supporting Russia; these parties have 10 percent of the seats in the national parliament.

In addition to sanctions, Russians are denied access to internet services from foreign providers [35], making Russian censorship more effective. At the same time, the Ukrainian government banned and blocked certain opposition voices. As the war progresses, the lesson from Georgia is that the flow of information to citizens might be a decisive factor.