A popular Mexican collective that digitizes books and shares them on its website as a political position is struggling with new copyright legislation. Since July 2022, the Pirateca website has been inaccessible through the country's main telecom operators.

This group is currently facing what they deem an act of persecution by government copyright authorities, which has led to a block on its website and restrictions in sharing related content on social media. Its Twitter account was also suspended.

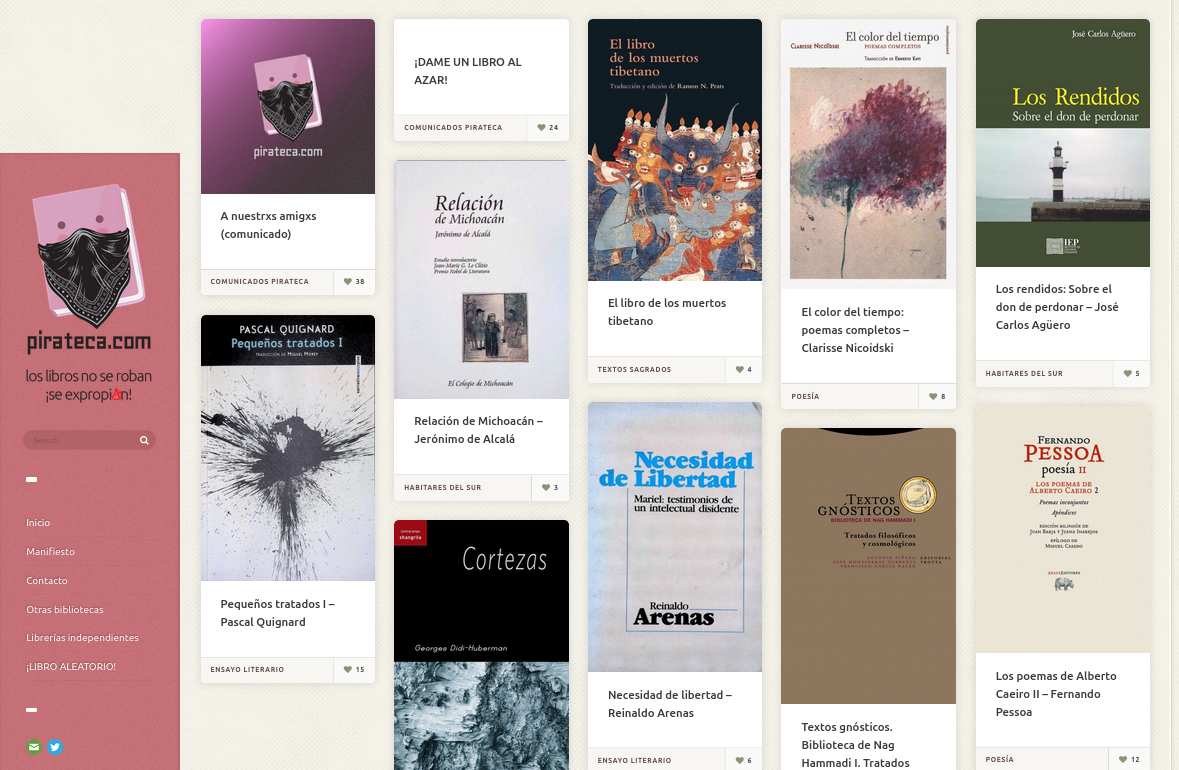

Since 2019, the Pirateca.com website has provided open access to more than 279 Spanish titles, under the slogan “Books are not stolen, they're expropriated!” Those managing Pirateca remain anonymous. They told Global Voices in their own words that:

A veces, para no centrar la atención en las identidades, preferimos decir que Pirateca no es nada. Pero tal vez, buscando una definición provisional, hoy podríamos decir: Pirateca es una amistad.

Sometimes, to avoid focusing on identities, we would rather say that Pirateca is nothing. However, in looking for a provisional definition, today we could perhaps say that Pirateca is a friendship.

The motivation behind this came from a desire to share the books that had left an impression on them:

Es nuestra forma de materializar el amor por nuestrxs amigxs, es el deseo de compartir nuestras lecturas con ellxs; pero también es el amor por esa comunidad posible, esa comunidad por venir: esxs otrxs amigxs que aún no conocemos, aquellxs con quienes en secreto, nuestros afectos resuenan.

This is our way of expressing love for our friends and a desire to share our reading material with them. However, it's also love for this potential, upcoming community: other friends we don't yet know, those with whom our sentiments secretly resonate.

Earlier this year, Pirateca readers noticed the website was unavailable on several of Mexico's telecom operators and thereby reported this on social media. They also maintain that Facebook had deleted old Pirateca posts and banned the creation of new ones.

As a mark of support towards Pirateca, several Mexican bookstores organized piggy banks for it to receive financial donations. These included the publisher and bookstore, Casa Impronta, which subsequently received a visit from the Mexican Institute of Industrial Property (IMPI) inspectors, who confiscated the piggy banks in the same month the blocks began.

The telecom operators involved in this block are the largest in Mexico: Telmex, Megacable, and at one point, Izzi, which stopped doing so thereafter. The historic network measurements of the Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI), a space dedicated to internet blocking documentation, and Ripe Atlas, both have records confirming this block. IMPI initiated this block after receiving an anonymous complaint concerning Pirateca, according to Pirateca's lawyer Salvador Alcantar.

The internet providers that Global Voices consulted, Telmex and Megacable, said that these blocking measures were due to the legal papers they had received from IMPI.

A Telmex spokesperson, Renato Flores Cartas, added:

Las medidas implementadas por TELMEX tienen como objetivo dar cumplimiento al requerimiento del IMPI y evitar la imposición de cualquiera de las sanciones previstas en el artículo 388 de la Ley.

The measures that TELMEX implements seek to comply with IMPI requirements and thereby avoid the imposition of any sanctions set out under Article 388 of the Law.

We consulted IMPI and its Assistant Director of Communications, Alberto Olguin, to find out more about the grounds and reasoning behind this procedure. Their answer was that this is an open and ongoing matter, thus making it impossible to provide any information on this case. Pirateca team members argue that these acts have an obvious ideological explanation:

[They seek] to perpetuate a profoundly classist system of privatization, which determines that only those with economic capital can access culture. For them, culture consists of any object that can be capitalized and owned. They reject a fact that we believe to be an absolute ontological reality: that any creation is always collective and that the value of cultural objects is in the lives it transforms, the hearts it touches, the minds it develops and not in the monetary value that any economic system may put on it.

Mexican legislation has undergone several copyright-related modifications. Since 2020, an administrative procedure makes it possible to request that telecom operators provisionally block access to websites, without having a court decision on the matter. In this instance, the blocking actions came from an administrative procedure rather than as the result of a trial. Alcantar considers this to be the country's first public case of this nature. He adds that one of the criticisms towards this new copyright legislation is that the authority does not have public records on this type of measure, thus meaning they can act at their discretion without any accountability.

In response to the economic argument that the way in which Pirateca shares books has an impact on the authors and publishers, the collective says:

Los derechos de autor no protegen a nadie más que a los intereses económicos de los dueños de los grandes capitales, o sea, a quienes menos participan en la elaboración de las potencias afectivas de un texto.

Copyright doesn't protect anyone other than the economic interests of significant capital owners, or rather, those less involved in devising the emotional power of a text.

They ask that the institutions and corporations that usually mention this argument should support it with public information on how the profits generated throughout the publishing industry are divided, in order to know the alleged impact of booksharing has on authors. The Mexican Publisher's Association (CANIEM) reported that the private book publishing industry generated an economic income of 8.469 billion pesos in 2020, 368 million of which were for e-books. The industry's economic strength remains paper books.

Thus far, the authority has not notified the collective about the legal grounds or accusations leading to their website's blocking, according to Pirateca. Pirateca maintains that the blocks are taking place amidst an act of persecution on the part of IMPI and CANIEM to find out the names of people running the collective and punish them. However, they confirm they will keep going thanks to the support they receive from those sharing books:

To be honest, we have become fearful. We have considered giving up on more than one occasion. Fortunately, our friends have never stopped encouraging and supporting us. It is for this reason we will keep going.