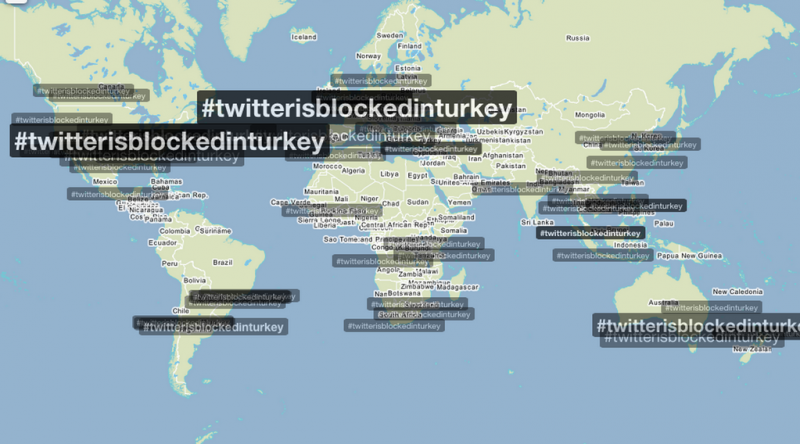

How the world saw Turkey's Twitter ban. Widely shared.

Twitter and YouTube were blocked in Turkey once again April 6, sparking plenty of fanfare across social networks.

This time around, the block was imposed after the mass circulation of photos from a hostage crisis that ended with the death of government prosecutor Mehmet Selim Kiraz and two leftist militants on March 31.

The block on Twitter was reportedly lifted the night of April 6 after the service complied with removal requests from Turkish authorities. Facebook was much faster to meet their requests and was blocked only briefly. Google also appears to have complied with a removal request based on a April 6 court order, escaping a block completely.

By some estimates, up to half of Turkey's population uses social media, with 12-14 million Twitter users alone. It is a huge market.

İbrahim Kalın, a spokesperson for Erdoğan, said in an official statement that banning social networks should not be seen as an attack on freedom of speech. BGN News quoted him as saying “it would be wrong to view the social media ban as a curbing of freedoms.” The intention of the blocks — triggered by court orders — was, in his words, to curb the “spread of terrorist propaganda.”

Protecting ‘family values’ (and the ruling party)

Since August elections, more than 70 people have been prosecuted for “insulting” President Erdoğan, in many cases on social media. During Erdoğan's time as Prime Minister, there were hundreds of such cases. Just prior to the hostage crisis, two prominent cartoonists of the weekly satirical magazine Penguen received 11-month prison sentences for “insulting” the president.

Ever since the Gezi protests went viral, Erdoğan's ruling AKP (Justice and Development) party seems to view Facebook, Twitter and YouTube as a giant stains on its reputation. After the killing of Prosecutor Kiraz on March 31, rumors spread that government leaks about the prosecutor's death which could potentially damage the party would soon emerge on social networks, although this has yet to prove the case.

Some Twitter users in Turkey were able to bypass mass censorship and access the site through proxies.

As @SpiritOfGezi pointed out:

3 MILLION tweets were posted in #Turkey since ban on twitter was imposed&still counting ;=) #TwitterisblockedinTurkey pic.twitter.com/5G1ODjFUty

— Spirit of Gezi (@SpiritOfGezi) April 6, 2015

But this does not apply to everyone — tech-savvy people are quick to find workarounds, but others are not so lucky. Analysts of the country's media space seem to agree that while the block is intended to decrease social media use in the country, authorities are perfectly aware that the block will not stifle conversation on Twitter altogether.

Folks tweeting about how the Twitter ban isn't working. The relevant comparison is with how much people tweeted before.

— Nate Schenkkan (@nateschenkkan) April 6, 2015

Turkish sociologist and media scholar Zeynep Tufekci suggests that the real goal of Erdoğan's campaign is to “demonize” social media and present it as a threat to “family values” and national unity. She writes:

Erdogan is not trying to block social media as much as taint it.

[…]

The battle isn’t between Internet’s ability to distribute corruption tapes and the government’s ability to suppress them. The battle is for the hearts and minds of Erdogan’s own supporters, and whether Erdogan can convince them that social media is a dangerous, uncontrolled, filthy place from which nothing good can come.

Since Erdoğan's election as president, he has moved to further limit the rights of netizens by changing laws affecting Internet rights. A soon-to-be-passed security law allows authorities to conduct broad-scale censorship and surveillance without prior judicial oversight.

What's more frightening is, today's ban comes even before amended Internet Law has come into effect. When it does, welcome ‘emergency rule'!

— YavuzBaydar (@yavuzbaydar) April 6, 2015

With Turkey getting closer to a general election, stirring a tense political atmosphere in the country, Erdoğan is looking for more ways to silence the people opposing him and AKP. Silencing opposition on social media brings them a step closer to this goal.

Playing the game

Al Jazeera Turkey reported Tuesday night, not long after the Twitter ban was lifted, that there was another Turkish court order aimed at Google. The court order gave Google four hours to remove all images related to the hostage crisis, or face a ban. At the time this article was written, a Google Image search shows far fewer photos of the prosecutor's kidnapping than before and — notably — the service did not get blocked.

According to Twitter's biannual Transparency Report, between July 1 and December 31, 2014, the Turkish government asked Twitter to withhold 2,642 tweets. In total, Twitter withheld 1,820 tweets requested by the government, amounting to 92% of the total tweets withheld by the service during that period. Moreover, accounts indicated by Turkey accounted for 72% of the accounts the service withheld during these six months.

Given its success with this approach, the Turkish government appears to have upped the stakes. Since Twitter's prior transparency report — covering activity from January 1 – June 30, 2014 — the service says: “We have received 156% more requests [from Turkey] with the number of accounts specified [for withholds] growing over 765%.”

Similarly shocking statistics are noted in Facebook's transparency report.

Currently it seems Twitter, Facebook and Google, far from damaging the image of the Turkish state, are actually doing their best to polish it.