Zaitokukai Anti-Korean March in Tokyo, March 2013. Image by Flickr user Kurashita Yuki. License: Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-SA 2.0)

The mayor of Osaka is taking on Internet hate speech — or at least trying to — one online video at a time.

For more than a decade, Osaka and other communities with large populations of ethnic Korean residents have struggled to deal with far-right organizations that target ethnic Koreans and other minorities through demonstrations and online campaigns.

Expressions of hate speech have stoked tensions between Japan and neighboring countries, and led to claims that Japan is not following its obligations under the UN's International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination.

The issue has surfaced repeatedly around online videos that put the activities and messages of these demonstrations on public display. The Asia-Pacific Human Rights Information Center transcribed and translated remarks made at a February 2013 rally and captured on a YouTube video, which has since been deleted:

Hello, all shit-Koreans living in Tsuruhashi. And hello to all the fellow Japanese present here. I hate the Koreans so much that I can’t stand it and I just want to kill them all now. If Koreans behave with this arrogance further, we will carry out Tsuruhashi massacre like Nanking massacre! (other participants shouted “yeah that’s right!”) If Japanese get angry, it will happen! We will start a massacre! Go back to your country before the massacre gets started! This is Japan, but not Korean peninsula! Go back! (other participants shouted “go back!”)

This video is just one among many. On June 1, the city of Osaka published the online username of another video blogger who the city says posted videos containing racially discriminatory hate speech, and thus violating the city's anti-hate speech ordinance.

According to the city of Osaka, a person working under the username ダイナモ (“Dynamo”), from an IP address located within Osaka city limits, uploaded a variety of videos where demonstrators at several different rallies repeatedly used offensive and defamatory words targeting Korean residents of Japan. The videos appeared on the popular Japanese sharing site, Nico Nico Douga on February 24, 2017.

In April, at the request of the Osaka municipal government, Nico Nico Douga removed two of the videos. A third video had already been removed by the blogger. Nevertheless, a panel of experts appointed by the mayor, as per the procedure outlined in Osaka's hate speech ordinance, recommended on June 1 that the city publish Dynamo's legal name and request the videos be removed from Nico Nico Douga.

As the videos had already been removed from Nico Nico Douga, this request was moot. But the panel's second request, to reveal Dynmo's legal identity. was not so easy to fulfill. Under Japan's current privacy laws, a city government cannot compel a sharing site (in this case, Nico Nico Douga) to provide the real name of user who has not committed a federal crime, as this goes against national privacy laws.

Osaka mayor Yoshimura Hirofumi publicly mused throughout the month of June about asking Japan's central government to somehow reform Internet privacy laws so that he could more directly expose Dynamo and make his/her actual identity known to the public. Yoshimura made headlines and briefly trended on Twitter at the end of June when he vowed to push Japan's national government to loosen Internet privacy laws.

Japanese daily Mainichi Shimbun reported that, on June 28, Mayor Yoshimura said that:

通信の秘密との兼ね合いがあるが「違法なヘイトスピーチを不特定多数に知らしめる人の氏名を保護する必要はない」

While it's important to protect the privacy of online communications, “there's no need to protect the (real) names of those who are communicating “illegal hate speech” to a wide audience.”

In the same interview, Yoshimura also announced he was considering introducing a motion in Osaka City Council in February 2018 that would revise and toughen the city's anti-hate speech ordinance (特定の民族や人種).

The mayor's ambitions come into conflict not only with guarantees of freedom of expression and assembly under Japan's Constitution, but also with Japan's Act on the Protection of Personal Information (APPI). The APPI provides strong protections for personal privacy online. For example, Japan's rules on data collection are so strict local authorities will sometimes not release the names of people listed as missing in flooding, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and other disasters, citing the need to protect personal information.

Why does Osaka get to make its own rules?

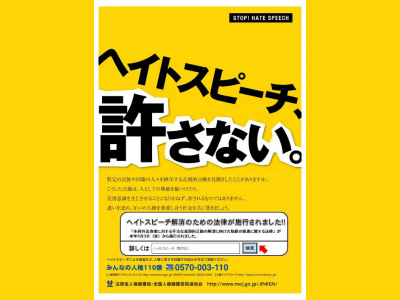

Japan's national parliament, the Diet, passed the country's first-ever law addressing hate speech in May 2016, within Japan's civil code.

The law does not ban hate speech and sets no penalty for committing it. Instead, it compels the central government, prefectures and municipalities (such as the city of Osaka) to devise measures against hate speech. So a month after Japan's national hate speech law was passed, the city of Osaka enacted its own, much tougher municipal ordinance targeting hate speech.

According to an unofficial translation by the Asia-Pacific Human Rights Information Center, a non-profit based in Osaka, the municipal ordinance defines hate speech by the following criteria:

(a) that it is undertaken for the purpose of any of the following:

i. to exclude individuals with particular racial or ethnic attributes or groups of such individuals (hereafter referred to as “particular individuals or groups”) from society;

ii. to restrict the rights or freedoms of particular individuals or groups; or,

iii. to incite hatred or discriminatory attitudes or violence against particular individuals or groups (when such a purpose is explicitly acknowledged).

(b) that its content or style falls under any of the following

i. it amounts to significant contempt or slander targeting particular individuals or groups; or,

ii. it threatens particular individuals or a significant number of the individuals of such groups;(c) that it is undertaken at a place or in a manner that makes it possible for the public to know its content.

The ordinance is targeted primarily at far-right groups such as the Zaitokukai (short for ‘在日特権を許さない市民の会’, Yurusanai Shimin no Kai, or “Citizens’ Group Opposed to Special Rights for Korean Residents of Japan). While anti-Korean sentiment has festered online in Japan for more than a decade, the Zaitokukai, now boasting 10,000 members, is relatively more recent. The far-right group gained notoriety in 2009 when it protested outside an ethnic Korean school in Kyoto.

Despite a Supreme Court ruling in 2014 against the Zaitokukai that levied fines and imposed a restraining order, similar demonstrations of nationalists targeting ethnic Koreans and other minorities have appeared in Tokyo and other cities.

Osaka's mayor says he will continue press the central government to increase punishments for people found to be publishing hateful content. In the meantime the Osaka panel will determine, if petitioned, if more hate speech activity is being committed online.