Virgin Mobile ad for Free Basics in Mexico. “Use Facebook for free with Free Basics / Connectivity for all”

When Facebook launched its Free Basics app aimed at helping people without Internet access, they said that the app would serve as an “on ramp” to using the whole global Internet.

But new research by Global Voices suggests that in contrast to this claim, the app primarily serves the needs of Facebook and other corporations, compromising user experience in order to achieve business objectives.

Free Basics today is a small set of apps within an app — it does not give them access to the full Internet, but instead offers a handful of web-based services, the most recognizable and prominent of which is Facebook.

Free Basics is currently available in 63 countries worldwide. In each market, it is provided through a partnership between Facebook and a local telecommunication operator. Operators provide a small amount of mobile data to customers, which can only be used to access Free Basics. Each country has a unique version of Free Basics, which is intended to provide adequate language support and content that is relevant for local users.

What kind of data does Facebook collect from Free Basics users?

Our research confirms that Free Basics grants Facebook access to unique streams of data about the habits and interests of users in developing countries. The company collects data about Free Basics users by monitoring their activities on Facebook — and throughout the Free Basics app.

In every version that we tested, users were strongly encouraged to log into Facebook, or sign up if they didn’t already have an account. The Facebook app appears at the top of the main page of the Free Basics app. And the app uses various tactics to encourage users to log in and keep up with their Facebook friends – for example, Colombia researcher Monica Bonilla reported the app automatically imported her Facebook account data because she had the Facebook app on her iPhone.

Free Basics permission screen in Ghana, via Tigo

But regardless of whether they log into Facebook, users of Free Basics are constantly sharing their data with Facebook.

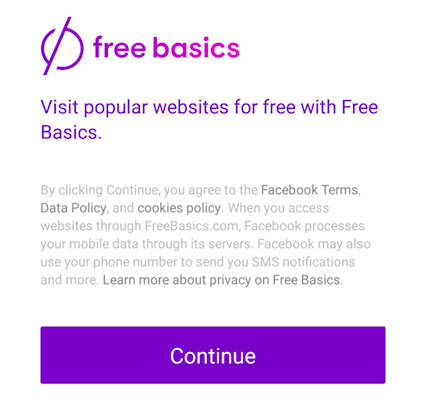

Our team learned this right at the start of our process. When a user launches the app for the first time, she must consent to various policies — terms of use, a data policy, a cookies policy and a product-specific privacy policy. We were surprised to find that all but one of these policies were written as agreements between the user and Facebook — not Free Basics.

How does Facebook collect this data?

On their website describing the initiative, Facebook explains that all traffic for Free Basics routes through an Internet.org proxy server, which standardizes the traffic flow for the app to let telco operators “zero rate” the traffic, a technical process that makes its transfer less costly.

This system gives Facebook a single node through which to collect and temporarily store users’ metadata. This means that users — whether they are accessing Facebook, or some other service within the Free Basics program — are sharing data with Facebook about what sites they visit, when, and for how long.

As with its regular services, Facebook appears to use this data in order to inform its choices about what kinds of information to promote in a user's feed. In Colombia, researcher Monica Bonilla observed that content in her Facebook newsfeed changed to reflect the content she had browsed in other areas of the Free Basics app.

Who else collects data from Free Basics users?

In the six countries where we conducted case studies, a plurality of the apps featured on the main page (see screenshot) of Free Basics belong to companies based in the United States such as ESPN, ChangeCorps and Johnson & Johnson, the creator of the “BabyCenter” app.

Screenshot of Free Basics front page in Kenya, via Airtel.

While the BabyCenter app offers users practical health information, it also provides the company with profitable data on users’ search behaviors and the interests and habits of potential customers — something that could compromise the scope or even the accuracy of the information provided.

In a 2014 interview, Johnson & Johnson global strategy manager Christina Hoff told AdWeek magazine that with BabyCenter, the company “can tell what a mom is going to do before she does [it] based on what she is searching for.” She explained how BabyCenter data had helped the company market pharmaceuticals to parents, and boasted that data from the app is more valuable than what the company learns from parents’ activities on Facebook and Twitter.

All versions we tested also offered local content in addition to corporate services from the US. While in some countries such as the Philippines, the app's main page included a wide variety of local content offerings, in others it did not.

In Mexico, the version of Free Basics offered by Telcel included only one local service on its main page: the website for Fundación Carlos Slim, the foundation of Telcel CEO and billionaire Carlos Slim. Mexico researcher Giovanna Salazar surmised that the app was deliberately featured on Free Basics in an effort to advertise and collect additional data from users.

All versions of the app that we tested contained many other services (typically between 120 and 150 per version) beyond those featured on the app's main page. But the majority of these services were relegated to a different section of the app, which is tucked away under a drop-down menu that users (especially first-timers) can easily miss altogether.

When we asked Facebook why they chose to divide services into two separate tiers, they declined to answer.

Telecommunications operators and ‘unspecified third parties’

In their policies, Facebook also reserves the right to share data with unspecified third parties. It is unclear whether this includes the telecommunications operators they partner with, but telcos gain access to valuable data through other means: for example, to use Free Basics a user must have a smart phone with a SIM card. In most of the countries we studied, purchasing a SIM card requires providing telcos with personal information such as your legal name and national ID.

The study raises a number of questions that still need answering: How much data is Facebook collecting through the app, and who is it sharing this data with? To what extent is this data collection helping Facebook and other corporations build new marketing strategies for developing countries?

We hope to answer these questions, and learn more about the app from Facebook's Free Basics team, in the months to come.