Image by Arzu Geybullayeva

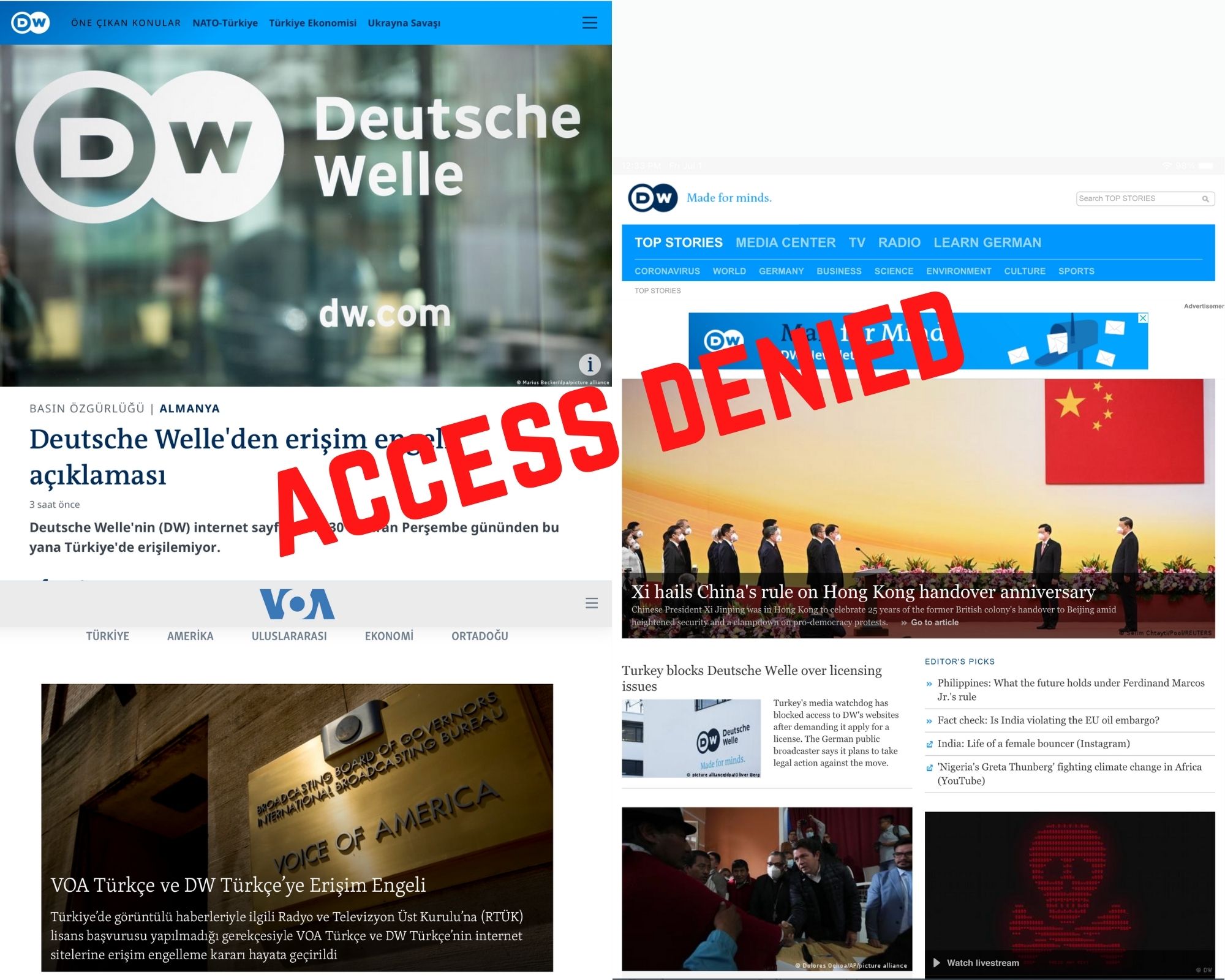

On June 30, Turkey’s Radio and Television High Council (RTÜK) — the main media watchdog — blocked access to the Turkish language websites of Deutsche Welle (DW) and Voice of America (VoA) after the two news outlets refused to obtain a broadcaster license. The decision comes months after Turkey’s media watchdog RTÜK said it would seek a court order to block access to the Turkish language services of DW, VoA, and Euronews. The announcement came after all three refused to apply for a broadcast license within the 72-hour period that the watchdog granted in February, 2022. In April 2022, after Euronews made adjustments to its website, RTÜK withdrew its request for the news platform.

“Turkey's media watchdog RTÜK has revoked the obligation on EuroNews to get their websites licensed. RTÜK grounded its decision on the fact EuroNews removed the content which allegedly necessitated a license. The process is yet to be completed for DW and VoA” @okonuralp https://t.co/WCbp5yavla pic.twitter.com/upwYb2shRv

— MLSA (@mlsaturkey) April 13, 2022

In recent years, RTÜK has been granted sweeping powers to control online media content. The move was not unusual, given that over 90 percent of mainstream media are owned by pro-government companies.

A new low yet again!

Turkish government bans VOA Turkish and DW Turkish.

The legal excuse is the lack of licensing, the real reason is both outlets becoming important sources of information since major Turkish media have been taken over by Erdoğan’s businessmen.#Turkey https://t.co/kSqOT7mzkF— Cansu Çamlıbel (@cansucamlibel) June 30, 2022

Yaman Akdeniz, a cyberlaw professor at Istanbul Bilgi University, described the decision as “censorship” in a series of tweets announcing the court's decision:

SANSÜR: Deutsche Welle ve Amerikanın Sesi haber sitelerine Ankara 1. Sulh Ceza Hakimliği, tarafından bu akşam erişim engellendi.

— Yaman Akdeniz (@cyberrights) June 30, 2022

Censorship: Ankara Criminal Court of Peace blocked DW and VoA news websites.

How Turkey got here?

In February, VoA and DW, announced their decision not to comply with RTÜK Regulations. In their statement, the Voice of America said:

Licensing is the norm for radio and TV broadcasting, because the broadcast spectrum is a finite public resource, and governments have a recognized responsibility to regulate the spectrum to ensure it is used in the broader public’s interest. The internet, by contrast, is not a limited resource, and the only possible purpose of a licensing requirement for internet distribution is enabling censorship.

DW’s statement echoed the sentiment:

After having subjected the local media outlets in Turkey to such regulation, an attempt is now being made to restrict the reporting of international media services. This move does not relate to formal aspects of broadcasting, but to the journalistic content itself. It gives the Turkish authorities the option to block the entire service based on individual, critical reports unless these reports are deleted. This would open up the possibility of censorship. We will appeal against this decision and take legal action in the Turkish courts.

The warning issued in February was based on a regulation that went into effect in August 2019 when the state granted RTÜK powers to monitor online broadcasting (ranging from on-demand platforms such as Netflix, to regular and/or scheduled online broadcasts to amateur home video makers), compelling online broadcasters to obtain a license from RTÜK.

In April 2022, Okan Konuralp, member of the RTÜK Council, speaking to Bianet, said the council may block access to DW and VoA “if the Ankara Penal Judgeship of Peace [Ankara Criminal Court of Peace] approves the request of RTÜK.” On June 30, the court ruled in favor of the access ban. This is the first time, RTÜK's powers were used to block online news said Can Guleryuzlu, president of the Progressive Journalists Association, in an interview with VoA.

Responding to the ban that has now taken place, DW’s director Peter Limbourg said, “DW will take legal action against the blocking,” in an interview with the Financial Times. Limbourg also said, in DW's discussions with the state watchdog the media platform tried explained “why it could not comply with the request to obtain a permit, including the fact that licensed media in Turkey are required to delete content that the watchdog deems inappropriate.” DW is now fully blocked in Turkey, including its international hyperlink.

In the meantime, VoA Turkish shared on Twitter how to circumvent the blocking using Psiphon and nthLink programs:

İnternet içeriklerine erişim engeli yaşandığı zaman Voice of America'yla (VOA) anlaşmaları da olan “Psiphon” ve “nthLink” program ve uygulamalarını kullanarak sansür ve engellemeleri aşıp internette istediğiniz içeriğe erişebilirsiniz pic.twitter.com/UriQjA1jkB

— VOA Türkçe (@VOATurkce) July 1, 2022

When access to internet content is blocked, you can bypass censorship and blocking and access the content on the internet by using the “Psiphon” and “nthLink” programs and applications, which also have agreements with Voice of America (VOA).

The sweeping legislative amendments to national laws as well as exhaustive institutional oversight by government institutions such as RTÜK have created an environment of unlimited digital censorship in a country, described by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), as the sixth-worst jailer of journalists according to the organization’s annual report from last year. Come fall, the parliament will also start the discussions on the draft media bill dubbed by the critics of the ruling government as the “censorship bill.”