La maison de la presse: lieu de la formation. Photo by Charlotte Noblet, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Fewer than 2 percent of Burundi’s 10.2 million residents use the Internet, but that hasn’t stopped the government from cracking down. This week, amid demonstrations, WhatsApp and Viber were reportedly blocked—at least by major telecoms—in the southeast African country.

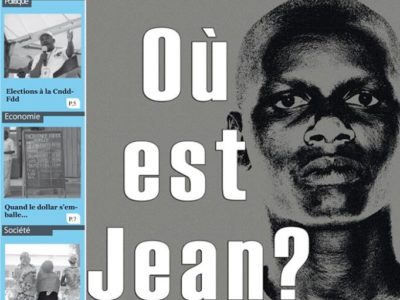

Protests began in the capital of Bujumbura last weekend after the ruling party nominated president Pierre Nkurunziza for a third term. In response to demonstrations, military troops were deployed to the capital and phone lines of private radio stations were cut, according to reports. More than 24,000 people have fled the country in the past month.

Why would a country with only 200,000 or so Internet users bother censoring conversational platforms like Viber and WhatsApp? The key is in the platforms’ use: Both platforms have allowed protesters in the capital to communicate quickly and privately. Whereas Twitter and Blackberry Messenger were popular during Egypt’s 2011 uprising, Burundians have instead turned toward the popular, but closed, messaging apps.

Although the blocking of these particular platforms may have been a first, restrictions on speech in Burundi are nothing new. In 2013, the government implemented a restrictive Press Law that requires journalists in the country to become accredited and reveal their confidential sources under certain circumstances, and imposes tight content restrictions requiring journalists to produce “balanced” reporting. It also allows for prior censorship, prohibits publication of anything relating to national security, and levies heavy fines on editors and journalists who violate the law. The law is currently facing a legal challenge from the Burundi Journalists’ Union and the Media Legal Defence Initiative.

Unfortunately, the latest censorship in Burundi might be part of a larger trend across the diverse continent. While Ethiopia continues its use of anti-terror laws to stifle dissent, Tanzania has just passed a draconian cybercrime law. There have been calls from Kenya to South Africa to “do something” about cybercrime, prompting the BBC to recently ask: “Can Africa fight cybercrime and preserve human rights?”

While the answer remains to be seen, we suggest our African readers visit the Electronic Frontier Foundation's Surveillance Self-Defense—a guide to protecting your communications online—now available in several languages, including French and Arabic.

A version of this post first appeared on the Electronic Frontier Foundation's Deeplinks blog.

3 comments