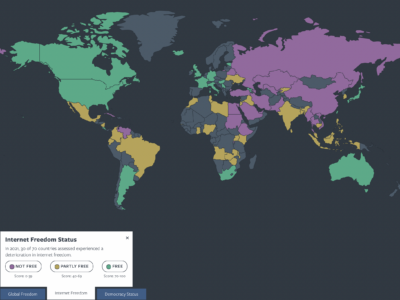

Nagorno-Karabakh map. Creative commons.

A relatively well-known Russian-Israeli travel blogger who is also a Ukrainian passport holder has been extradited from Belarus to Azerbaijan for visiting a territory that fell under the de facto control of Azerbaijan's neighbour, Armenia, following a war between the two countries that began while they were both part of the Soviet Union. He faces eight years in jail.

If it isn't already clear, it should be said now that this is a story that gets very complicated, very quickly.

In drafting this report Global Voices owes a debt to another, better-known Russian blogger: Ilya Varlamov, who put together a fantastic ‘What Do We Know?’ type-piece when Aleksandr Lapshin, a travel blogger who claims to have visited 122 different countries, was still in detention in Belarus in January.

Given the complexities of the case, it makes sense to proceed in the same vein as Varlamov did, by answering the immediate questions raised by the case.

What does Azerbaijan say Alexander Lapshin has done?

According to the Azeri state prosecutor, Lapshin faces up to eight years under charges of “making public calls against the state” and “illegally crossing the state borders of Azerbaijan”. Moreover, the Russian agency Sputnik cites the prosecutor:

Он пропагандировал незаконный режим, действующий на оккупированной территории Азербайджана, на своей странице, где представлял Нагорный Карабах как независимое государство. 6 апреля и 29 июня 2016 года Лапшин публиковал на своей странице обращение, в котором призывал поддержать “независимость” незаконного режима на захваченной Арменией территории Азербайджана, территориальная целостность которого признана на международном уровне.

[Lapshin] propagated the illegal regime acting on occupied Azerbaijani territory on his [Facebook] page, where he presented Nagorno-Karabakh as an independent state. On April 6, and June 29, 2016, Lapshin published on his page an appeal wherein he called for support for the “independence’ of the illegal regime acting on the territory seized by Armenia, whose [ownership by Azerbaijan] is internationally acknowledged.

Has he really done those things?

Regarding the first charge, “making public calls” against the Azerbaijani state, which is a charge that opponents of authoritarian governments in countries across the world face, Varlamov notes that this is difficult to verify. A trusted friend has been updating Lapshin's regular blog since his detention in Belarus began, but the entries neither deny nor confirm that these posts were written.

It is likely that Lapshin subsequently deleted the Facebook posts referred to by the Azerbaijan prosecutor, but it is perhaps worth noting that Lapshin does not list Nagorno-Karabakh among the “countries” he has visited on his blog, as a serious advocate of the territory's independence might.

It is, at any rate, very bizarre that Lapshin has been extradited to face charges for making a “call” against a state where he was not born and has not held citizenship and most likely was not located when he made that “call”.

Thus it seems more likely that the official legal justification for extradition was the second charge, “illegally crossing the state borders of Azerbaijan”, which he is technically guilty of.

As Azerbaijan still claims jurisdiction over Nagorno-Karabakh (and indeed, the UN is on its side on this point) the Azerbaijani government demands that anyone wishing to visit the country applies for permission first.

Lapshin appears not to have done this prior to trips there in 2011 and 2012, and subsequently got added to a blacklist preventing him from entering Azerbaijan proper. However, he flaunted this ban by entering on his Ukrainian passport in which he is called Oleksandr rather than Aleksandr, thus avoiding detection by Azerbaijani border guards. He then boasted of this feat in a post since taken down, which led Russian blogger Ilya Varlamov to conclude that the moral of Lapshin's detention was “don't be a moron”. Varlamov later reversed this judgement when readers of his blog argued that it was overly harsh.

For those unfamiliar with the complexities of Caucasus travel, Lapshin himself wrote in a post just before the 2011 trip to Karabakh that is still online:

Прилетаю в Ереван, но сразу же выдвигаюсь в Азербайджан через Грузию. Такой расклад не случаен, ибо, как известно, азербайджанские пограничники крайне ревностно относятся к теме армян и Карабаха. Очень многие туристы задержитвались азербайджанским ГБ при въезде в страну и досконально обыскивались и допрашивались, едва лишь у них находили армянские печати в паспортах. При этом для отказа во въезде в страну (и даже задержании на сутки-двое) вполне достаточно что бы у них возникло подозрение, что вы посетили Карабах, который они считают своей, но незаконно оккупированной территорией. Из этого мораль – зачем рисковать и прятать карту памяти из фотоаппарата, где будут явные свидетельства посещения Карабаха? Ведь при желании – найдут в два счета и будут неприятности. Таким образом, проще переиграть все наоборот и начать с Азербайджана, потом Грузия, и завершить вновь в Армении.

I will fly into Yerevan, but will immediately move onto Azerbaijan via Georgia. […] As you know, Azerbaijani border guards are extremely sensitive to the topic of Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia. Many tourists have been detained by Azerbaijani security services when entering the country and thoroughly frisked and interrogated, purely because they found an Armenian stamp in their passports. They may refuse you entry to the country (and even detain you for a day or two) if they have any reason to suspect that you visited Nagorno-Karabakh, which they consider an illegally occupied territory [of Azerbaijan]. So, why risk [crossing] and hiding the memory card of the camera, which would clearly show evidence of visits to Nagorno-Karabakh? It is much easier for me to start with Azerbaijan, then move onto Georgia, and finish again in Armenia [in order to visit Nagorno-Karabakh].

Why did Belarus decide to extradite?

Lapshin was detained on December 13 by Belarusian authorities on the basis of an Interpol warrant requested by Azerbaijan. He was held for almost two months before being extradited to Azerbaijan on February 7.

Interpol often honours the requests of authoritarian governments to place their political enemies on its list, often only removing them from the list when third party countries hold them before releasing them. So, no surprises that Lapshin was put on the list and subsequently detained by Belarus.

Belarus’ decision to hold for such a length of time — Lapshin's friend has claimed mistreatment during the detention but not torture — before extraditing is far more curious, and international affairs may have played a role.

Officially, Belarusian President Aleksandr Lukashenka has said the decision to extradite was carried out “in accordance with the law”. But it seems unlikely that this was a result of due process. Belarus has held individuals placed on the Interpol list by friendly countries before — sometimes for long periods of time — and later released them.

The key in this instance might be the objection of Russia to both the detention and extradition of its citizen Lapshin. Belarus and Russia's up-and-down relationship was in a trough at the time of Lapshin's detention, and has only gotten worse since.

Russia's foreign ministry said on February 8 that it was “deeply disappointed” with the decision to extradite, which went against “the spirit of friendly ties between allies — Russia and Belarus”. But anyone that watched snippets of Lukashenka's recent press conference lasting over seven hours and packed with anti-Kremlin vitriol would hardly describe those ties as friendly at present.

Israel also opposed the extradition, while Ukraine, which needs all the international support it can get in the face of aggression from Moscow (especially from other ex-Soviet states like Belarus and Azerbaijan) has chosen not to say anything.

Eight years? Really?

Probably not. Worth noting is an interview given by pro-government Azerbaijani national security expert Kyamil Salimov to the local arm of Russian government-owned media outlet Sputnik on February 8. In it he said:

Поэтому я здесь вижу только то, что лидеры Азербайджана и Беларуси продемонстрировали политическую уверенность в урегулировании процесса. Не думаю, что в отношении Лапшина назначат чрезмерно жесткое наказание. Скорее всего, президент Азербайджана проявит гуманизм в отношении него.

I see only that the leaders of Azerbaijan and Belarus displayed political confidence in regulating this question. I don't think that in the case of Lapshin there will be some kind of strict punishment. Probably, the president of Azerbaijan will show him mercy.

Judging by the on-message nature of Salimov's other interviews, it is likely his thinking and the Azerbaijan government's own thinking are probably in harmony. A heavy sentence would dramatically raise the international profile of a case that has so far only skimmed the surface of the international media's attention, and draw sharp criticism from the West. More pressingly, Azerbaijan has good reasons to keep long-time ally Israel on side, as well as Russia, which has armed both parties in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.

Unquestionably though, it will be a nervy wait for Lapshin, a travel blogger whose naive dabbling in politics has already seen him held in confinement by two of the world's worst rights abusers.

Nagorno-Karabakh, again.

Lapshin's arrest is proof — if any was needed — that Azerbaijan is in no hurry to soften its stance on Nagorno-Karabakh, which was part of its territory in Soviet times, despite ethnic Armenians there outnumbering ethnic Azeris by about 4 to 1 prior to the bloc's break up.

Last year saw some of the worst fighting over the territory since the conflict formally ended in 1994 and Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev (or one of his staffers) has in the past taken to Twitter to threaten an all-out invasion.

Armenia, in turn, has few incentives to hand the beautiful but landlocked would-be-state back to Azerbaijan given a lack of significant pressure to do so, notably from Russia, which is widely seen as an arbiter in the conflict.

The risk of war between the two countries remains real, and this passage from the Accidental Geographer blog on their standoff as depressingly relevant as ever:

This. pic.twitter.com/qOxesobIWt

— Karena Avedissian (@KarenaAv) April 2, 2016

2 comments

Hundreds of thousands of people, if not millions, have visited the independent Republic of Nagorno-Karabagh (Artsakh) since 1991/1992, and will continue to do so, as they should. This includes European, American and OSCE officials.

Cruel, despotic Azerbaijan will never regain control.

By the war, Belarus lies. There was no Interpol arrest warrant for Lapshin.

Azerbaijan has repeatedly warned foreigners of unauthorized visits to its Nagorno-Karabakh region occupied by Armenian forces, calling them contradictory to international law.