President Yoon Suk Yeol and First Lady Kim Keon Hee bid farewell before departing for the United Kingdom on September 18, 2022. Seoul Air Base, Seongnam-si, Gyeonggi-do. Photo by JEON HAN from the KOCIS Flickr page. (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 DEED).

You may have encountered the metaphor of the boiling frog. The tale suggests that a frog in a pot of slowly heated water will not perceive the immediate danger and will ultimately be boiled alive. Although this has been debunked as more myth than scientific fact, the metaphor remains potent.

South Korea is recognised as a well-established country economically, politically, and technologically. International indices typically reflect this, showing stable and consistent rankings with no significant fluctuations. However, this article aims to highlight the country’s recent regression in media and free speech environments, a troubling undercurrent not fully reported in global analyses.

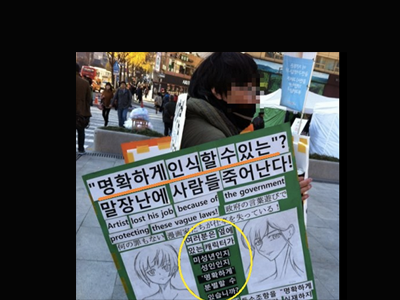

The current conservative government, which assumed office in May 2022, has faced accusations of employing tactics that create a chilling effect on free speech. Chief among these accusations is retaliation against journalists and news organisations critical of President Yoon Suk Yeol, First Lady Kim Keon Hee, and their ministers under the pretext of spreading fake news. Reports include instances of barring dissenting journalists from press briefings and subjecting them to investigations on defamation and election interference based on their coverage of alleged malfeasance by Yoon and Kim. Some situations have even escalated to raids on the journalists’ homes and offices.

Prosecutors raid Newstapa, JTBC over fake interview allegations https://t.co/9ZhShu6XQr

— Yonhap News Agency (@YonhapNews) September 14, 2023

This retaliatory approach was foreshadowed in January 2022 when a leaked phone conversation during the presidential campaign captured Kim threatening to incarcerate all journalists opposed to her husband if he were elected.

Moreover, President Yoon has issued an unprecedented number of enforcement decrees, surpassing his predecessors at the same point in their terms. In South Korea’s legislative framework, while the constitution is the supreme law and acts passed by the National Assembly embody constitutional values, administrative legislation like presidential decrees are executive instruments designed to operationalise these acts. Such decrees, which must not conflict with higher laws, have jurisdiction over all administrative affairs. Yoon’s use of these decrees has often allowed him to appoint allies to influential positions, sidestepping the requirement for assembly approval. The most recent decree, enacted in October 2023, restricts rallies and gatherings near the presidential offices.

The government’s controversial appointments include Lee Dong-gwan as the new head of the state broadcasting watchdog, the Korea Communications Commission (KCC), and Park Min as the new head of the government-funded national broadcaster, the Korean Broadcasting System (KBS). Both appointees have vowed to eradicate “ideological biases.” Concurrently, the administration has intensified its rhetoric against “fake news,” a move that has become more pronounced with the upcoming legislative election in April 2024.

The leader of the People Power Party, of which President Yoon is a member, has condemned certain liberal media outlets, claiming that their biased reporting undermines the nation’s democracy and equates to high treason warranting the death penalty. In its quest to be the arbiter of truth, the government has sought to manage the public narrative, especially in relation to its handling of disasters, both natural and man-made. Notable incidents include the tragic crowd crush in Itaewon, Seoul, during the 2022 Halloween festivities, resulting in at least 159 deaths and 196 injuries, and the inadequate responses to the July 2023 floods in Osong and Yecheon, which led to significant casualties and a Marine corporal’s death, respectively. The victims’ families have continued their tireless search for accountability, to little effect.

The government’s narrative efforts extend to historical perspectives. The Yoon administration’s stance reflects a significant pivot from traditional commemorations. The recent belittling of Hong Beom-do, a celebrated anti-colonial hero who fought against Japanese occupation in the 1920s, alongside the glorification of Syngman Rhee, the country’s first president known for his stringent anti-communist policies, indicates a shift towards a narrative that aligns more closely with US and Japanese interests. This rewriting of history not only marginalises the legacy of resistance against Japanese occupation but also seems to strategically recast the country’s past to facilitate contemporary geopolitical alliances.

The Yoon administration, along with the People Power Party, has also attracted criticism for fostering misogyny and hate speech, allegedly integrating such rhetoric into their election campaigns, social media engagement, and policymaking. The recent surge in anti-feminist sentiment has led to job losses for women and even physical assaults. Meanwhile, President Yoon has courted controversy with his proposals to abolish the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family and to diminish labour protections, particularly for immigrant workers. Additionally, the president and his wife have reportedly associated with far-right YouTubers, offering them invitations to the presidential inauguration, sending holiday gifts, and even appointing them to government roles.

Reflecting on the proverbial frog — and a similar Korean adage that suggests one may not notice a drizzle until getting drenched — each of these political shifts alone might not seem like an immediate threat, and none are overtly illegal or authoritarian. Yet, their cumulative effects raise concerns about the country’s democratic stability. With national elections on the horizon, the government’s tightening grip on public dissent and media oversight will be a critical test of the country’s commitment to democratic principles and civil liberties.