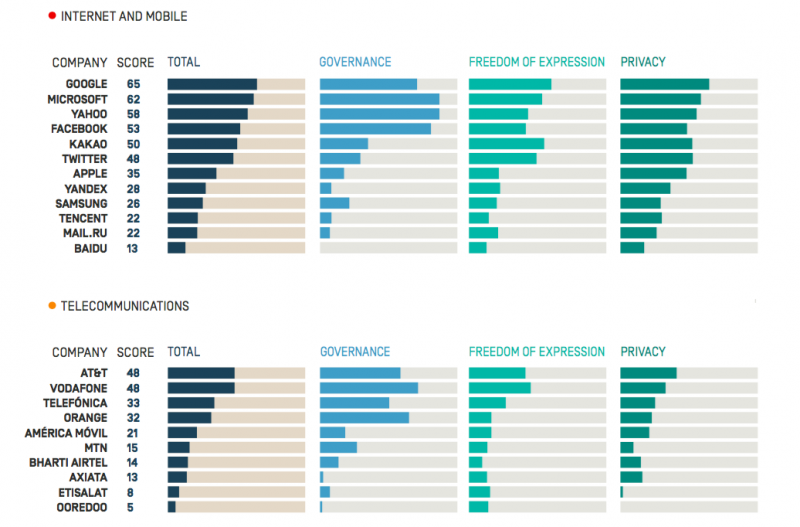

Ranking Digital Rights Corporate Accountability Index 2017 – overall scores for companies.

Global Voices Advocacy's Netizen Report offers an international snapshot of challenges, victories, and emerging trends in Internet rights around the world.

In mid-March Indian documentarian Rakesh Sharma, who is known for his films on public unrest and violence in the state of Gujarat, found his YouTube channel blocked. He received a message from the company that read:

This account has been terminated due to multiple or severe violations of YouTube’s policy against spam, deceptive practices, and misleading content or other Terms of Service violations.

The channel had been live since 2014 and mainly features clips from his documentaries, which have garnered considerable attention in India, Europe and the US. Two days later, without explanation, the channel was back on. Sharma is known for his critical views on Indian PM Narendra Modi, which are evident in his films, but there’s no evidence to prove this had anything to do with the block.

Indeed, there’s no information — beyond YouTube’s boilerplate takedown text — explaining what motivated the sudden blocking and equally sudden reappearance of the channel.

Sharma isn’t alone. Amid an apparent shift in YouTube’s approach to monitoring for rules violations (with a particular focus on extremist content) and staying in the good graces of advertisers, a wave of YouTube users have found their work either blocked or relegated to “restricted” mode in recent months.

YouTube video bloggers whose work includes themes of same-sex relationships and LGBT acceptance and rights are among those who have found their videos suddenly unavailable in “restricted” mode, an opt-in version of YouTube intended for children and school computer labs. Users are voicing concern and posting examples of the blocks under the #YouTubeIsOverParty hashtag on Twitter.

The blocks raise critical questions about the partly technical, partly human-driven process that YouTube uses to spot videos that violate its terms or qualify as inappropriate for younger viewers. While some types of content — such as videos clearly intended to be pornographic — are easy to identify and remove, others are not. And in many cases, the process begins with YouTube users themselves, who are free to report content if they think it’s breaking the rules. This mechanism plays a powerful role in how the company sets priorities for content removal — and it sometimes results in abuse by users intent on silencing people they disagree with.

These examples illustrate the importance of corporate transparency surrounding content removal decisions, both on the individual and platform-wide level. The issue is emphasized in the Ranking Digital Rights Index for 2017 (released this week), which measures against a comprehensive set of international human rights standards as they exist in the digital realm.

Iranians see new threats to speech as elections approach

Iranians are seeing a crackdown on press freedom and digital expression leading up to the May 2017 presidential elections. Iran’s Revolutionary Guards, a hardline wing of the armed forces that answers to the office of the Supreme Leader, arrested 12 administrators of channels on the messaging app Telegram that support Iran’s reformist political faction, as well as those behind the moderate President Hassan Rouhani.

Telegram developed a significant Iranian user base approaching the 2016 parliamentary elections and many believe it helped facilitate gains for reformist and moderate members of parliament. Iranian authorities have been trying to curb the free flow of information through Telegram both with arrests and with new rules that require media organizations and journalists to obtain an official license in order to distribute news through Telegram.

On top of this, authorities recently arrested two journalists, Ehsan Mazandarani and Hengameh Shahidi, both of whom are known for their independent and critical reporting.

Jamaican women’s rights activist arrested for social media campaign tactics

Jamaican activist Latoya Nugent was arrested last week and charged under Jamaica's Cybercrimes Act for “use of a computer for malicious communication” after she publicly identified alleged perpetrators of sexual violence via social media. Nugent is the co-founder of Tambourine Army, a new movement led by women and survivors of sexual violence who are talking openly about their experiences, both online and in public. In an editorial for the Jamaica Gleaner, legal scholar Tenesha Myrie called this section of the Cybercrimes Act “an attempt to criminalise defamation through the back door,” noting that offline, defamation is treated as a matter of civil — not criminal — law in Jamaica.

Guatemalan news site attacked after posting interviews with fire survivors

A house fire that killed 40 young women at a shelter on the outskirts of Guatemala City on March 8 drew significant media attention in the region and beyond, but coverage of the story by local outlets did not go unpunished. Guatemalan independent news site NomadaGT, which published recorded testimonies from two young women who survived the fire, suffered what appeared to be a DDoS (distributed denial of service) attack, leaving the site offline for several hours.

UAE activist arrested for “publishing false information”

On March 20, authorities in the United Arab Emirates detained Ahmed Mansoor, a respected human rights defender who was the 2015 laureate of the Martin Ennals Foundation, which supports human rights defenders at risk. Mansoor stands accused of using social media “to publish false information and rumors as well as promoting a sectarian and hate-incited agenda.”

On March 15, an Abu Dhabi court convicted Jordanian journalist Tayseer al-Najjar of “insulting symbols of the state” on social media, which is a crime under the 2012 UAE Cybercrime Law. The case against al-Najjar focused primarily on a Facebook post that he published in 2014, while still living in Jordan, where he criticized the Emirati position in the 2014 war in Gaza.

Brazilian blogger forced to disclose sources to federal judge

A leftist Brazilian blogger named Eduardo Guimarães had a laptop and two phones confiscated after he released key information about a confidential anti-corruption investigation in Brazil. A supporter of former President Lula and a leading figure among left-wing activists and politicians, Guimarães released information that was allegedly leaked from the investigation of the Operação Lava Jato (Operation Car Wash) corruption scandal. The blogger says he also was asked to disclose his sources, triggering a wave of online protests in the country's blogosphere (including from right-wing bloggers) and reports in major media outlets concerning the protection of sources. Reporters Without Borders noted on the BBC that this is a “serious attack” on media freedom in Brazil.

Court rules US citizen can’t sue Ethiopian government for putting spyware on his computer

A US court of appeals ruled that a US citizen, who goes by the pseudonym Kidane, cannot sue the Ethiopian government for hacking into his computer using the targeted spy software FinSpy. The decision hinges on the court’s interpretation of where the hacking occurred: it ruled that though Kidane, who is Ethiopian-born, opened the infected email attachment in the United States, the placement of the virus began outside the United States.

Kidane’s lawyer, Electronic Frontier Foundation staff attorney Nate Cardozo, said the court is simply wrong in this interpretation and called the ruling “extremely dangerous for cybersecurity.” The EFF said they are evaluating their options on appealing the ruling.

Internet freedom activists targeted by Ben Ali regime speak at Tunisian Commission

Tunisian blogger Zouhair Yahyaoui, who founded the satirical TUNeZINE online forum, was jailed and tortured for publishing “false news” in 2001. Now his story has been brought light as part of a series of public hearings on human rights violations under the dictatorship of Zine El-Abidine Ben Ali, who governed Tunisia for 23 years until his January 2011 ousting.

Bloggers, activists and relatives of those who were targeted by the Ben Ali regime testified before Tunisia’s Truth and Dignity Commission, which dedicated a special session to the issue of online rights violations. It remains unclear whether and how Tunisia’s transitional justice process will impact future Internet policies, but for a country once described as an “Internet enemy”, acknowledging its abusive past is an imperative first step toward reform.

New Research

- Corporate Accountability Index 2017 – Ranking Digital Rights

- Educating, hiring and retaining women in technology: A gendered enquiry – Radhika Radhakrishnan

- The State of Internet Censorship in Thailand – Open Observatory for Network Interference

Subscribe to the Netizen Report by email

Afef Abrougui, Mahsa Alimardani, Ellery Roberts Biddle, Weiping Li, Leila Nachawati, Diego Casaes, and Sarah Myers West contributed to this report.

1 comment